Sweltering heat waves have blanketed Southeast Asia and other regions recently. One contributing factor has been record-breaking ocean temperatures. Oceans have thus far absorbed the brunt of global warming- trapping 93 per cent of excess heat in the biosphere. Ocean warming, along with overfishing, has already caused fish stock depletion by between 15 and 35 per cent over the past eight decades even as global populations grew from 2 to 8 billion.

Unfortunately, record ocean temperatures are not the only issue of concern. Ocean acidification, sometimes called the “evil twin” of climate warming, is another result of rising greenhouse gas emissions.

Ocean acidification refers to the drop in pH levels in seawater, which were on average 8.2 in the pre-industrial era. Since then, it has declined by 0.1 units. While this appears minute, because the pH scale is logarithmic, this actually represents a 30 per cent increase in acidity. Mid-range projections for 2100 is that ocean pH could decline by 0.3 to 0.4 units. This would be devastating for ocean biodiversity. As a comparison, a drop in blood pH in humans by 0.2-0.3 units could cause seizures, comas and even death.

The main cause of acidification is higher oceanic levels of dissolved carbon dioxide (CO2) — the main gas responsible for rising temperatures and climate change. Oceans currently absorb over 25 million tonnes of CO2 daily; cumulatively it has absorbed approximately 31 per cent of anthropogenic CO2 since industrial times. Other contributors to acidification, particularly at estuaries and ports, include agriculture runoff, sewage contamination, eutrophication, ship discharges, and plastic leaching. The latter is particularly acute in Southeast Asia, as the region contributes about a third of global marine plastic waste. Organic acids are released when sunlight hits aged plastic, leading to localised pH decreases of up to 0.5 units.

Unfortunately, record ocean temperatures are not the only issue of concern. Ocean acidification, sometimes called the “evil twin” of climate warming, is another result of rising greenhouse gas emissions.

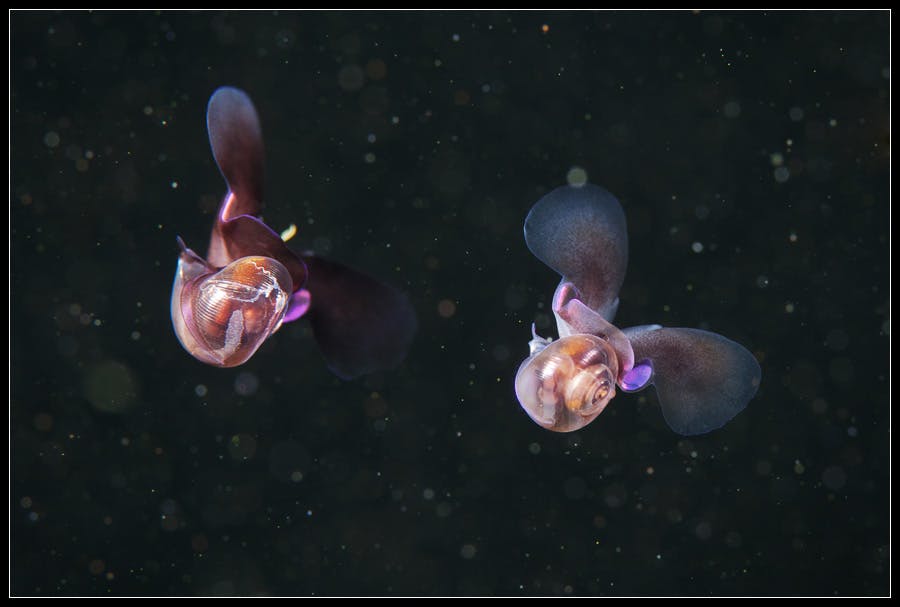

Sea Butterflies (Limacina helicina), a vital zooplankton, experienced deformities and mortalities as a result of ocean acidification Source: Alexander Semenov, Flickr

Ocean acidification refers to the drop in pH levels in seawater, which were on average 8.2 in the pre-industrial era. Since then, it has declined by 0.1 units. While this appears minute, because the pH scale is logarithmic, this actually represents a 30 per cent increase in acidity. Mid-range projections for 2100 is that ocean pH could decline by 0.3 to 0.4 units. This would be devastating for ocean biodiversity. As a comparison, a drop in blood pH in humans by 0.2-0.3 units could cause seizures, comas and even death.

The main cause of acidification is higher oceanic levels of dissolved carbon dioxide (CO2) — the main gas responsible for rising temperatures and climate change. Oceans currently absorb over 25 million tonnes of CO2 daily; cumulatively it has absorbed approximately 31 per cent of anthropogenic CO2 since industrial times. Other contributors to acidification, particularly at estuaries and ports, include agriculture runoff, sewage contamination, eutrophication, ship discharges, and plastic leaching. The latter is particularly acute in Southeast Asia, as the region contributes about a third of global marine plastic waste. Organic acids are released when sunlight hits aged plastic, leading to localised pH decreases of up to 0.5 units.

Two, it impacts fish physiology and impairs behaviour. For example, the pacific salmon and clownfish were found to lose their abilities to differentiate between prey and predator or locate suitable habitats respectively. This eroded their survivability.

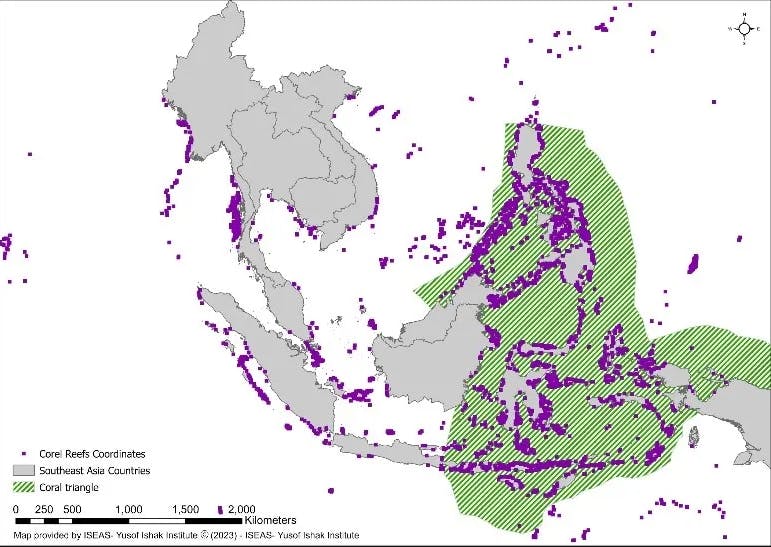

Lastly, acidification reduces coral reef viability. The lower pH results in coral skeletons losing structural integrity. Eventually, this leads to the collapse of reefs, akin to corrosion of load-bearing pillars in buildings. Reefs are the habitats of many fish species. They also provide coastal protection (reducing erosion and storm-wave impact), tourism revenue and other cultural and economic values. One study has suggested that coral reefs in Southeast Asia provide an estimated US$10.6 billion in economic benefits.

Southeast Asia holds 34 per cent of the world’s coral reef ecosystem and houses the coral triangle, which has more coral reef fish biodiversity than anywhere else in the world. Image: UNEP-WCMC, WorldFish Centre, 2021/ Fulcrum

Altogether, the impact of ocean acidification is critical to ocean health and food security. Notwithstanding the need for an immediate cessation of greenhouse gas emissions and pollution, interventions are crucial to avoid irreversible damage.

A major impediment to successful interventions is the sparseness of localised marine water quality data and records. As acidification rates are slower in the warmer tropics compared to cooler poles, localised research is imperative to clarify impacts. While one study in the US has projected that acidification could result in the loss of oysters and scallops by 50 and 55 per cent respectively by 2100, similar research is not yet possible in Southeast Asia due to lack of data.

Fortunately, there is some data. Some entities are collecting data. These include global bodies such as the IOC Sub-Commission for the Western Pacific (WESTPAC) and the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network, as well as localised networks such as the Marine Environment Sensing Network. However, these are still insufficient. As a priority, regional efforts to set up sensors and localised analysis centres are vital to set baselines and measure the effectiveness of interventions. The Southeast Asia Fisheries Development Centres (SEAFDEC), the ASEAN regional body to promote sustainable fisheries and aquaculture in SEA for example, could potentially coordinate research.

Solutions are possible. One laboratory study has identified that the seaweed Chaetomorpha antennina can reverse pH decline. It has antibacterial and bio-stimulant properties and can be found in the waters of Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. More studies are needed to identify if it is a viable solution.

Where acidification is most rapidly affecting coral reefs and fisheries, the restoration of coastal blue carbon ecosystems — mangroves, seagrass meadows and coastal marshes — as well as coral propagation, could provide alternative fishery habitats and coastal protection. Expanding investment in resilient, sustainable aquaculture can contribute to seafood availability for food security. More than 60 per cent of Southeast Asians live within 60 kilometres of the coast and are intrinsically linked to its resources. Ocean warming and acidification will not only impact food security, but also culture, well-being and livelihoods. It is thus crucial that collective action is taken to build ocean health before the damage becomes irreversible.

Elyssa Kaur Ludher is Visiting Fellow with the Climate Change in Southeast Asia Programme, ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute. Prior to joining, Ms Ludher contributed to food policy research at the World Bank, Centre for Liveable Cities Singapore, and the Singapore Food Agency.

The author would like to thank Dr Jani Tanzil, Senior Research Fellow & Deputy Facility Director, and Dr Ow Yan Xiang, Senior Research Fellow, both from the St John’s Island National Marine Laboratory Singapore, for assistance and factual review of this commentary.

This article was first published by ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute as a Fulcrum commentary.