This story is part of our Decoding Sustainable Finance series, where we attempt to break down complex terminology surrounding the latest regulations and trends in sustainable finance.

Doubts are starting to surface over the credibility of targets embedded in sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) coming to market. The concerns over greenwash are sparking a response from standard-setters keen to ensure confidence in what many market participants still consider a promising financing instrument meant for holding companies accountable to their climate targets.

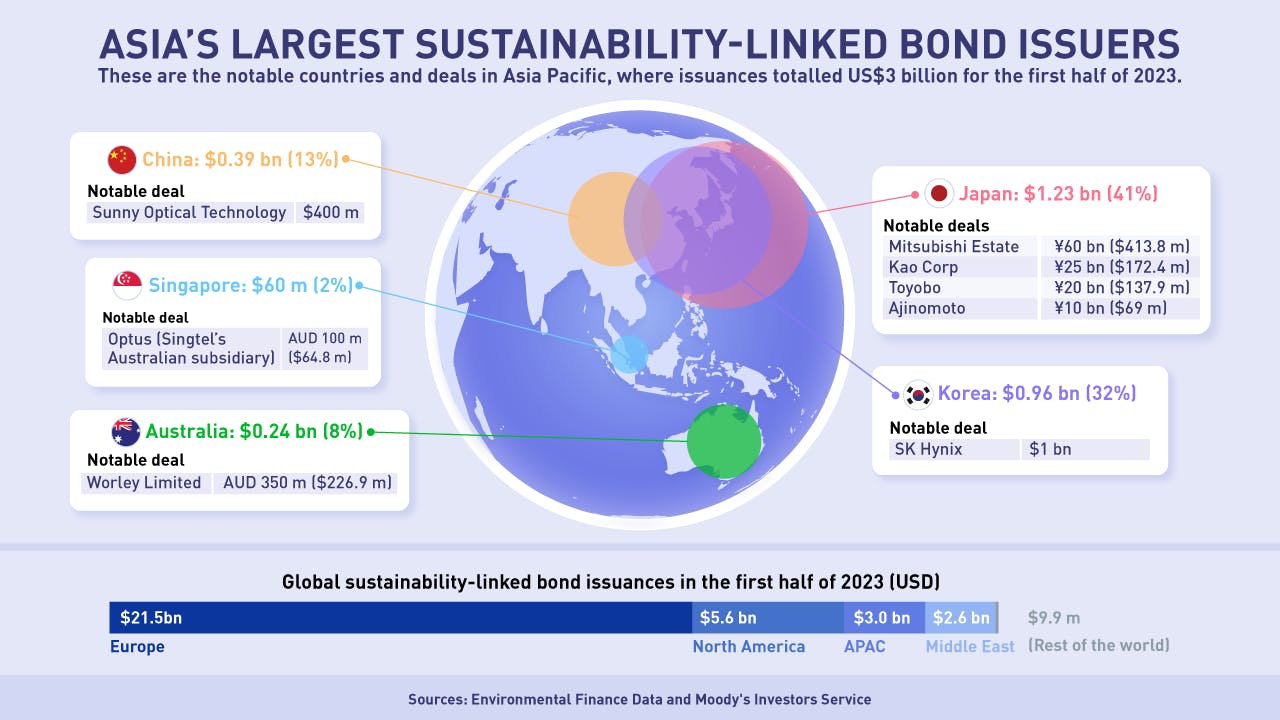

Increasing investor scrutiny, alongside macroeconomic uncertainty, has led to a slowdown in SLB issuance last year. In the first half of 2023, global SLB issuance further declined by 28 per cent year on year, according to credit rating agency Moody’s.

To continue reading, just sign up – it’s free!

- Get the latest news, jobs, events and more with our Weekly Newsletter delivered to you free.

- Access the largest repository of news and views on sustainability topics.

- You can publish your jobs, events, press releases and research reports here too!

Newsletter subscribers do not necessarily have a website account. Please sign up for free to continue reading!

While the nascent SLB market in Asia Pacific – which currently accounts for less than two per cent of the region’s total sustainable bond issuances – also saw a similar decline, analysts remain optimistic about its growth prospects. The continued market focus on “quality over quantity” may also bring about a gradual comeback in volumes, they say.

Eco-Business looks at the greenwash concerns around the increasingly popular transition finance structure and how issuers, investors and regulators can ensure that SLBs can be used credibly to finance the net-zero transition in Asia.

What is a sustainability-linked bond?

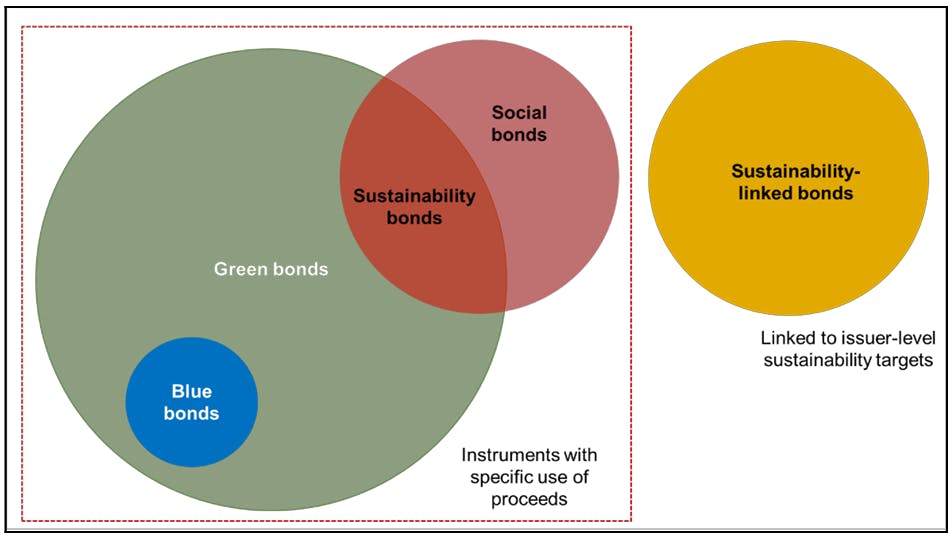

As a financing mechanism, SLBs have surged in popularity among issuers in hard-to-abate sectors, such as the industrial or material sectors, which typically find it more challenging to access sustainable financing through green, social and sustainability (GSS) bonds. GSS bonds rely on the use-of-proceeds approach, where the issuer must promise to investors that all raised funds go to projects with specified environmental or social benefits, such as renewable energy plants or climate mitigation programmes.

Sustainability-linked bonds have no specific use of proceeds, unlike green, social and sustainability bonds, but are tied to the issuer’s sustainability targets. Source: OCBC Credit Research

In contrast, SLBs are not restricted in how proceeds are used, but require the issuer to set explicit sustainability performance targets (SPTs) and key performance indicators (KPIs) to meet within a given time frame before the debt matures. Some frequently used KPIs include a reduction in carbon emissions and an increase in renewable energy consumption or production.

In order to incentivise issuers to achieve these targets, they need to be linked to a change in the bond’s financial or structural characteristics, such as a variation in the interest payments to investors. In short, SLBs can offer lower interest rates to issuers if they are able to meet the specified performance targets.

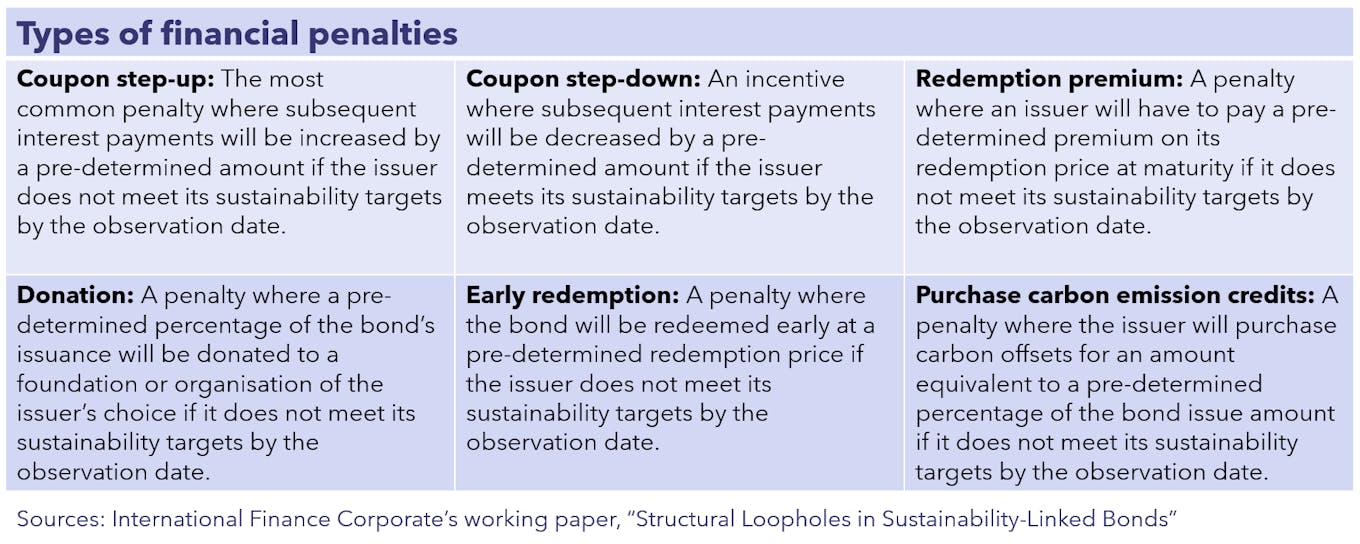

Typically, if an issuer fails to meet its targets, it will have to pay a higher coupon to investors, also known as a “step-up” penalty. A minority of SLBs have other penalty structures.

On the whole, SLBs are designed such that they reinforce accountability from issuers. These issuers are made to “have skin in the game” in achieving strategic sustainability objectives once they choose to use the financial instrument, according to trade body International Capital Markets Association (ICMA).

Step-up coupons are the most preferred penalty type by issuers, followed by a redemption premium and step-down coupons. Image: Gabrielle See/Eco-Business

State of SLB issuance in Asia Pacific

In the first half of 2023, Asia Pacific made up nine per cent of the global SLB market, with issuances worth US$3 billion. The growth of the region’s issuances has slowed since the second half of 2022 due to market volatility and growing investor scrutiny globally around the credibility and ambition of SLBs being issued.

Asia’s largest SLB issuances in the first half of 2023. Image: Philip Amiote/Eco-Business

The recovery of SLBs in APAC is expected to be bolstered by increasing policy and regulatory focus on transition finance, where jurisdictions like China, Japan, Singapore and Southeast Asia have increasingly focused on defining transition activities. This year, ICMA also updated its guidance for SLBs, which it introduced in 2020, as well as its Climate Transition Handbook, as part of its efforts to harmonise transition financing standards.

Why the concern over greenwash?

Currently, greenwashing in the SLBs market is not a widespread phenomenon, according to analyst Cedric Rimaud who tracks developments in Asia Pacific. The senior credit analyst from climate think tank Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute (AFII) said: “Many sectors are genuinely working on reducing their carbon footprint. By and large, the targets used for SLB frameworks are specific, driven by data, focused on decarbonisation and verified by third parties.”

“Where greenwashing does occur, it is usually through the misrepresentation of pathways to real decarbonisation,” Rimaud told Eco-Business. Some examples include issuers having targets that omit Scope 3 emissions, changing the reporting parameters before the results are evaluated, or being intrinsically linked with a group that continues to be responsible for significant carbon emissions.

There have, however, been high-profile cases globally that has called to attention the importance of strengthening the credibility of SLBs. In January 2023, global advocacy organisation Mighty Earth filed a complaint with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) against Brazilian meatpacker JBS, accusing it of misleading investors with US$3.2 billion worth of SLB issuances that were raised based on commitments to cut emissions and achieve net zero by 2040, but excluded the company’s Scope 3 emissions, which made up the bulk of its emissions.

The SLB pioneer Enel – which launched the world’s first SLB in September 2019 – has also been flagged for not being entirely transparent with investors when it changed its 2017 baseline for calculating its sustainability performance targets this year while retaining old targets, meaning that a less drastic reduction in carbon emissions is needed to achieve its targets.

In Asia, last November, AFII raised concerns over the sale of Singapore-based energy provider Sembcorp’s Indian coal power plants held by its subsidiary Sembcorp Energy India Limited (SEIL) in its bid to avoid higher interest payments on SLBs totalling S$975 million (US$718.9 million). The institute had questioned Sembcorp over whether investors were made aware that the decarbonisation of the coal firm would take place through the sale of the assets, rather than transitioning them to less carbon-intensive alternatives.

Imtiaz Ul Haq, an economist at International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private investment arm of the World Bank Group, told Eco-Business that “many SLBs contain structural features that could allow issuers to minimise or evade financial penalties for missing sustainability targets”. Ul Haq described these as “structural loopholes” in a working paper that examined all SLBs issued till the end of 2021. The paper identified three loopholes: low penalties, late target dates and call options.

IFC’s analysis found that over half of SLBs with step-up penalties have a coupon penalty of exactly 25 basis points, which is a source of concern as it suggests the arbitrary nature of setting the penalty amounts. The average penalty among SLBs with step-up penalties – the most extensively used penalty type by issuers – is only around 12 per cent of the coupon rate, which is “a relatively small incentive”, said Ul Haq.

“Furthermore, most SLBs with step-up penalities tend to delay penalties until the last few years before bond maturity, reducing the total cost of the penalty imposed,” he said.

About six in ten SLBs were found to have a call option, which allows issuers to buy back or cancel a debt before the deadline to meet its targets. SLBs are also three times more likely to be callable than green bonds and five times more so than conventional corporate bonds, which indicates a potential loophole, Ul Haq said.

Sean Tseng, a legal consultant at international environmental law charity ClientEarth also highlighted the absence of legal guardrails in SLBs, which widens the scope for greenwashing. “Other than the coupon step-up, which has its own limitations, there is a lack of legal rights or remedies for the investor in relation to the sustainability-linked promises of the issuer,” he said.

“While frameworks like ICMA’s Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles provide helpful guidance, these are voluntary. Often, the economic incentives to issue SLBs unrestricted outweigh any moral inclination to comply with any of these standards,” Tseng said.

“

“What the market is calling out for are credible and verifiable SPTs, which are not undermined by disclaimers which allow for proceeds to be used for entirely unrelated purposes, and legal guardrails to protect investors’ expectations.”

Sean Tseng, legal consultant, ClientEarth

Rimaud shared similar concerns in the context of Sembcorp’s SLBs, where investors have little legal recourse to claim that a coupon step-up might be due since the SLB framework, which is based on voluntary principles, is not usually part of the legal documentation of the bonds. In 2025, the observation date of Sembcorp’s SLBs, Rimaud expects investors to question why the coupon has not stepped up and for the country’s financial regulator Monetary Authority of Singapore and Singapore Exchange to “review the terms of the documentations and assess whether the issuer has acted in full faith to the SLB investors.”

“Despite the proliferation of voluntary standards, frameworks and guidelines, these have to-date been insufficient to address the problems of greenwashing in SLBs. We imagine that enforceable standards and requirements issued by regulators or accountability mechanisms provided by issuers in the instruments would help combat greenwashing,” said Tseng.

“What the market is calling out for are credible and verifiable SPTs, which are not undermined by disclaimers which allow for proceeds to be used for entirely unrelated purposes, and legal guardrails to protect investors’ expectations,” he said.

Here are some suggestions on how issuers can use SLBs credibly:

1. Have ambitious SPTs

Rimaud recommends that an issuer use Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) or other science-based metrics to establish their sustainability objectives. “If possible, get it validated by a third party,” he said. “The more ambitious their targets, the more willing the investors will be to invest in these instruments, possibly offering a lower cost of capital for achieving strong targets.”

Tseng highlighted how Climate Bonds Initiative, an international non-profit organisation that promotes investments to combat climate change, now offers Sustainability-Linked Debt Instrument certification, which can certify ambitious targets and credible transition plans.

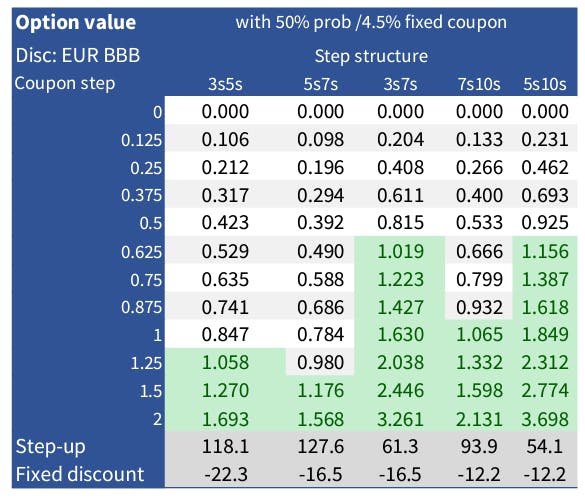

2. Have meaningful financial incentives

The Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute’s “greenback SLB” pricing model, which shows that the coupon step-up would need to be in excess of 51.8 basis points for an SLB with a five year observation date and five year pay-out period to reach “greenback” status (highlighted in green in the table above). Source: AFII’s “Greenback SLBs: an impact standardisation proposal”

To make pay-outs financially material, the AFII has proposed a “greenback SLB”, or a SLB where the present value of the coupon step-up, under a probability function of the issuer hitting its sustainability targets, is at least a dollar in bond price terms (i.e. one percentage point). This addresses cases where the pay-out of a SLB is not financially material (i.e. low coupon step-up), the trigger point of a SLB is too close to the maturity date (i.e. short accruals) or the SLB lacks ambition (i.e. low probability of a step-up).

Ul Haq also recommended a structure that limits the issuers’ ability to minimise penalties post-issuance to drive meaningful outcomes.

3. Have effective legal guardrails built in

ClientEarth is currently working with industry experts to design legal guardrails for bond issuers and investors, including template clauses that can encapsulate meaningful climate-related commitments with clear accountability mechanisms. Some examples of these legal guardrails include not allowing for disclaimers where proceeds from the bonds could be applied for purposes other than those for which it was issued and considering whether penalties should attach to interim targets provided in the SLB.

“These can enhance certainty for both parties at the point of issuance and over the lifetime of a bond. This kind of certainty is important for the market if climate-related representations are to be elevated to commitments that can be effectively valued and priced,” said Catriona Glascott, who is leading this effort for ClientEarth.

4. Clearly disclose how SPTs will be achieved

This can be done through roadshows for new SLBs, where issuers can share how the targets were selected and how they will be achieved. Investors can then “exercise robust stewardship” at the point of financing or refinancing a bond to ensure it reflects their requirements and mandates, said Tseng.

Keen to learn more about the latest trends and developments in the sustainability space? Find out more at Unlocking Capital For Sustainability, our annual flagship event.