This story is part of our Decoding Sustainable Finance series, where we attempt to break down complex terminology surrounding the latest regulations and trends in sustainable finance.

In 2015, “blended finance” was launched as one of the approaches to financing the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at the Third International Conference on Financing for Development in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Eight years on, even as it features high on the agenda in many high-level public meetings and policy papers, blended finance has yet to live up to its promise of filling the financing gap.

To continue reading, just sign up – it’s free!

- Get the latest news, jobs, events and more with our Weekly Newsletter delivered to you free.

- Access the largest repository of news and views on sustainability topics.

- You can publish your jobs, events, press releases and research reports here too!

Newsletter subscribers do not necessarily have a website account. Please sign up for free to continue reading!

To date, blended finance has mobilised nearly US$198 billion towards sustainable development in developing countries, according to data from Convergence, a Canada-based blended finance network. This amounts to barely one per cent of the annual climate and SDG funding needs in developing countries, an amount that stood at US$2.5 trillion pre-pandemic, and has grown to US$4.2 trillion per year since 2020.

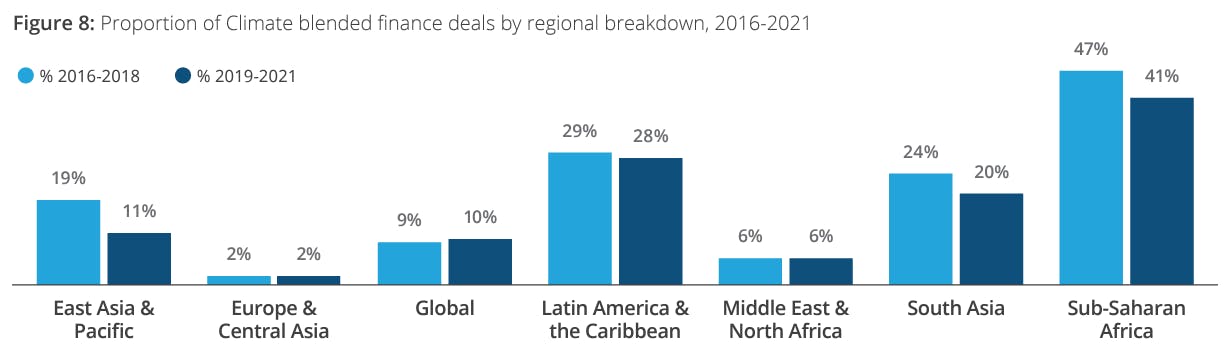

Climate-focused blended finance has taken a hit in recent years, despite mounting rhetoric around mobilising private capital for climate action. Between 2019 and 2021, Convergence data showed that there were only US$14 billion worth of climate-related blended finance deals for poor countries, less than half the volume seen in the previous three years.

Regional breakdown of climate blended finance deals between 2016 and 2021. East Asia and the Pacific experienced the highest proportional decrease during this period. Source: Convergence’s State of Blended Finance 2022 report

Eco-Business looks at what is holding blended finance back and how it can be scaled up to bridge the sustainable development funding gap for developing countries in Asia.

What is blended finance?

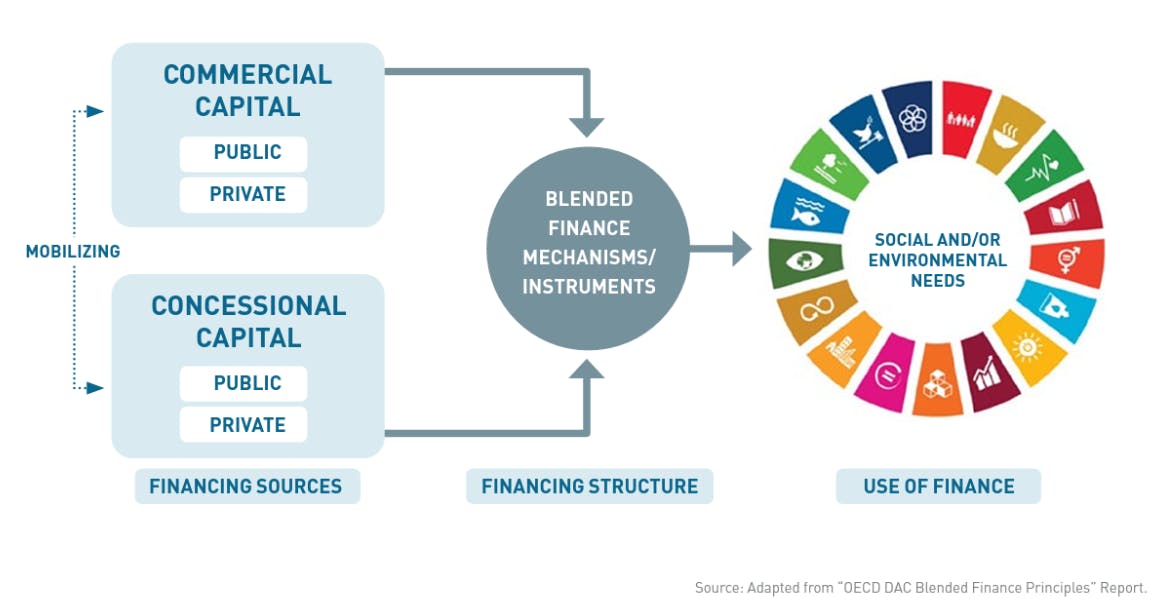

Blended finance is a structuring approach (not to be confused with financing approaches and instruments) that allows organisations with differing objectives – be it financial return, social impact, or a blend of both – to invest alongside each other. It is meant to attract and de-risk private investment in developing countries to realise the SDGs through the strategic use of public or philanthropic sources of capital.

Blended finance structures bring together two types of capital: concessional and commercial. Source: OECD DAC Blended Finance Principles

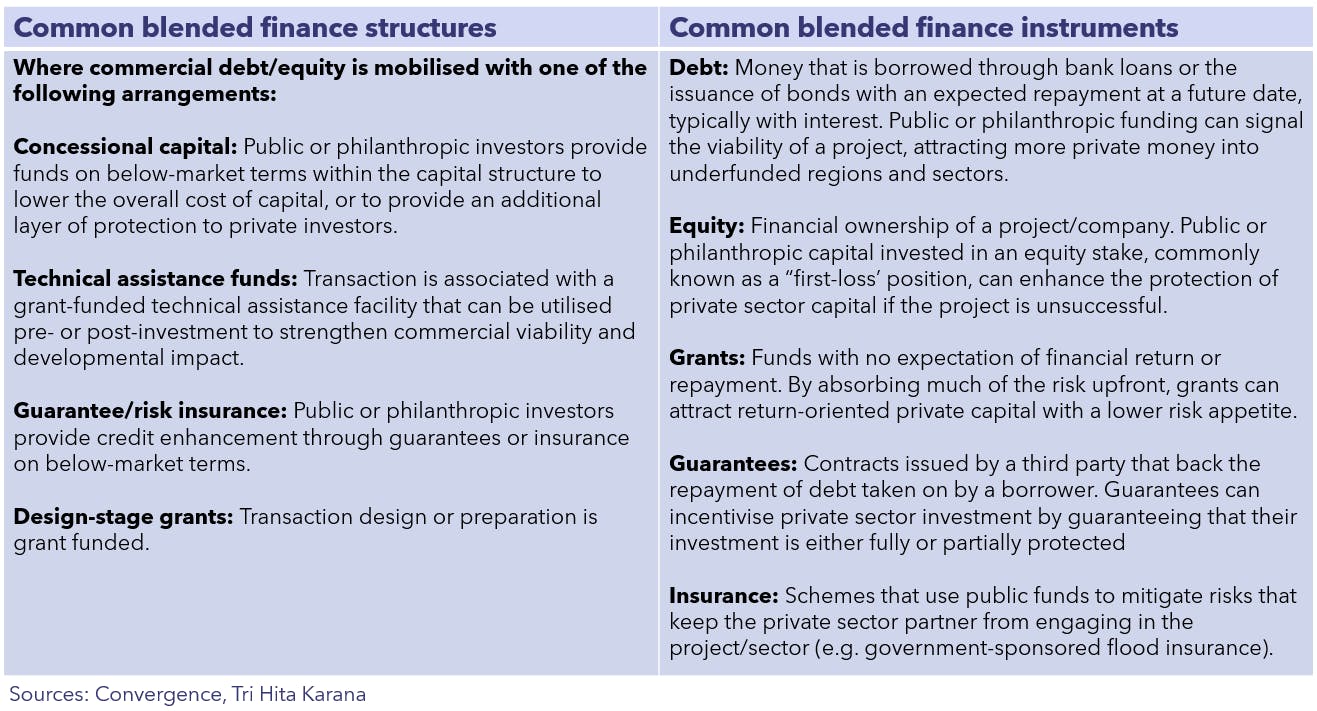

Concessional capital, usually provided by governments, multilateral development banks (MDBs), development finance institutions (DFIs) and philanthropic investors, can accept less favourable rates of return and absorb more risks in order to draw in private capital. This type of capital can take the form of investment-stage grants and first-loss debt or equity. It is by far the most popular among the four main “blends” that Convergence has identified, the others being technical assistance funds, guarantees and design-stage grants.

On the other hand, commercial capital, which comes from private investors like banks, asset managers and impact investors, often has market-rate return expectations. In this case, traditional investment instruments such as loans and equity instruments are often used.

Different blended finance structures can use a variety of financial instruments to mobilise private capital towards projects and sectors in order to meet the sustainable development goals. Image: Gabrielle See / Eco-Business

Japan’s Green Finance Organisation (GFO), which runs the country’s green fund and makes equity investments that bear the first loss in local clean energy projects, is an example of blended finance. One of the first national green investment banks to launch in Asia in 2013, GFO has invested US$123 million into projects with a total value of over US$1 billion as of March 2018. This means that for every US$1 in public investment, it has secured US$11 from the private sector.

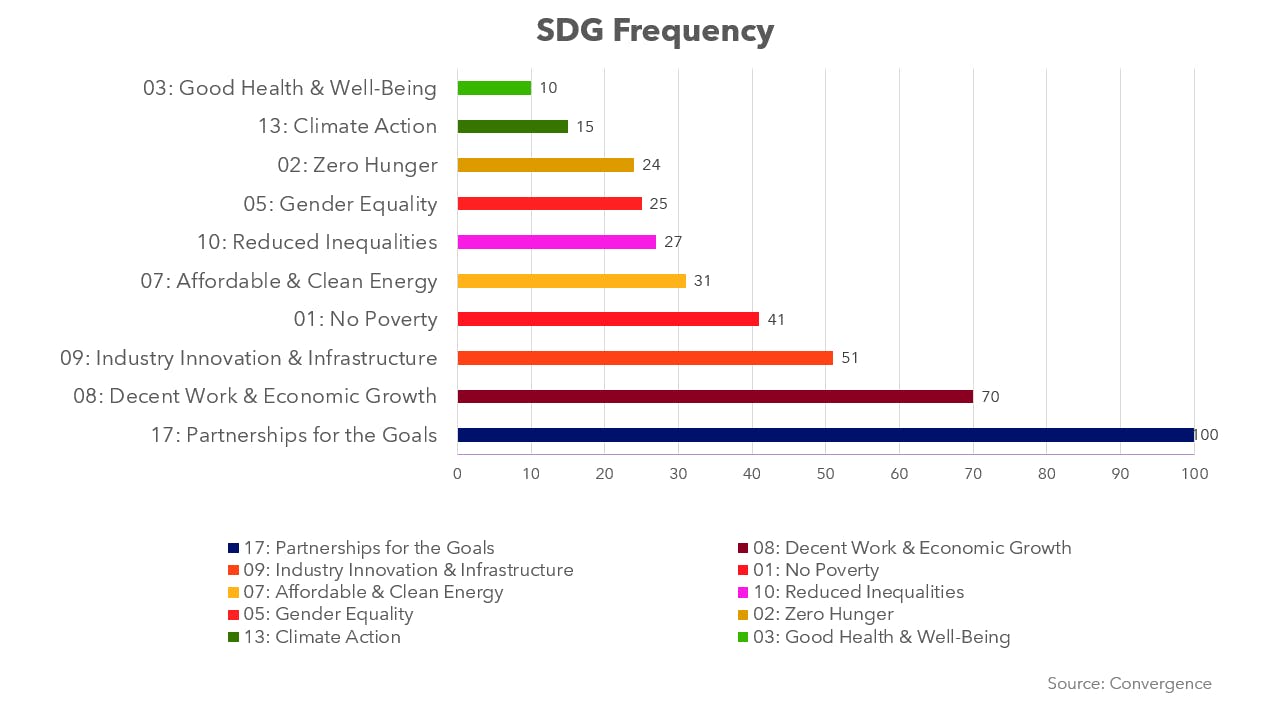

Of the 17 SDGs, Goal 17 (partnership for the goals) has been the most frequently targeted in blended finance transactions, while Goal 13 (climate action) and Goal 3 (good health and well-being) have been the least targeted.

The uneven spread of blended finance deals across the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Image: Gabrielle See / Eco-Business

While Sub-Saharan Africa has been the most frequently targeted region in blended finance deals, making up nearly half of the world’s transactions, Asia and Latin America have emerged as new hotspots for blended finance in recent years.

As of 2022, the Convergence database has recorded 107 blended finance transactions that make up US$20.7 billion in committed financing that target the Asean region in part or in full. Indonesia – which accounts for over a third of the deals in the region – is Asean’s largest blended finance player in terms of deal count and aggregate financing, followed by the Philippines, Vietnam and Cambodia. Renewable energy is the key sub-sector in Asean’s blended finance deals by volume.

The largest commercial investors in Asean by deal count are the Asian Development Bank (ADB) – which accounts for a fifth of blended finance deals – and the World Bank’s private sector arm International Finance Corporation (IFC). Meanwhile, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) are the largest providers of concessionary funding.

Finding the right blend

The success of blended finance rests on the ability to maximise additionality, both in terms of the financial resources mobilised and the developmental impact created, while minimising concessionality, or providing public capital at as close to market conditions as possible.

This ensures that the concessionary capital does not crowd out commercial capital and achieves development impact that would otherwise not have materialised without the intervention.

The design of blended finance transactions needs to take into account context-specific drivers of additionality, concessionality, mobilisation and commercial sustainability, as laid out by the OECD’s guidance note on designing blended finance. These include geography, sector, stage in the project cycle, market maturity and financial instruments chosen for the transaction.

For instance, in developing countries with higher risk profiles, blended finance has higher additionality and may require a higher share of concessionality. Sectors, like renewables, with established regulatory and investment frameworks, a track record of private investment and underlying financial sustainability might also be able to successfully attract commercial capital without the need for further de-risking through blended finance.

Monica Bae, director of investor practice at the Asia Investor Group on Climate Change (AIGCC) said that while institutional investors do have large amounts of capital and can provide patient capital, they still have fiduciary obligations to their clients. AIGCC has members representing over US$11 trillion in assets under management, including Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund GIC.

Bae said that structuring deals cannot expect private capital to be concessionary or grants. Instead, “the right conditions, including attractive risk-adjusted returns, policy credibility and predictability, and investment size” are needed to unlock the billions of dollars held by institutional investors, she said.

Lack of investable projects, standardisation and transparency

“For many Asian markets, the discussion should pivot from ambition to implementation,” said Bae, who cited that the types of investable options for private investors are limited in Asia, despite strong consensus that blended finance is crucial to accelerate a just energy transition.

Bae explained that most blended finance transactions currently happen in small- to mid-sized markets, but institutional investors often look out for complementary large investments of private and public capital in deals within a sector of the economy, given their capacity to deploy capital in the millions and billions of dollars.

“

“For many Asian markets, the discussion should pivot from ambition to implementation.”

Monica Bae, director, Investor Practice, Asia Investor Group on Climate Change (AIGCC)

This echoes the call for “portfolio approaches” to play a bigger role in scaling private investment volume and balancing risk allocation for private investors through blended finance deals by a 2022 OECD paper, which examined the constraints in scaling up blended finance in developing countries.

An example of this approach is the IFC’s Managed Co-Lending Portfolio Programme, which allows institutional investors to participate in deals originated by the IFC in infrastructure projects in developing countries, for instance. With the support from Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), IFC is able to provide limited first-loss guarantee on investments to meet the risk-reward profile that institutional investors like German insurance giant Allianz SE and Prudential’s Asia-focused asset management arm Eastspring Investments require.

The need for blended finance deals to be highly contextualised has also meant that the structures are often not readily replicable and scalable.

“While bespoke transactions are important to showcase and innovate, scale can only be reached in repeat transactions,” wrote the OECD paper, which pointed to the need for a more standardised approach to blended finance projects to bring down due diligence and hence transaction costs, which can support the scaling of portfolio approaches.

In addition, the lack of data and transparency on deal flow, project risks and performance has impeded the private sector’s participation in financing net zero-aligned projects in emerging markets and developing economies, noted Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), the world’s largest coalition of financial institutions committed to net zero by 2050.

There is one significant data source: the Global Emerging Markets (GEMs) Risk database. Established by IFC and the European Investment Bank (EIB) in 2009, it has become the world’s largest credit risk database for emerging markets business of international financial institutions, including the credit default rates, risks of credit downgrades and the average amount that can be recovered from defaulted projects funded by these institutions.

However, this database remains accessible only to participating organisations. Although those active in the mobilisation community, like Convergence’s managing director Chris Clubb, have been asking for this information to be made available for private investors for the last six years, the project’s owners have reportedly refused.

“If private investors had that dataset, it’s possible that a lot more lending would have happened. The release of this in our estimation would have saved probably more than US$5 billion a year in interest by governments in low-and-middle income countries,” Clubb said.

According to Clubb, it is also unclear how much private investment DFIs and MDBs have mobilised from private third-party financing, as much of the private sector finance leveraged is likely their own private sector operations or sponsor money. Convergence’s own research that looked at 72 blended finance funds found that only US$1.10 of US$4 of commercial capital leveraged from each dollar of concessional funding came from private sector investors.

But IFC has clarified that its private mobilisation figures do not include any DFI own-account funds or public funds, though they include sponsor money. It also discloses the estimated amount of concessionality applied in each blended finance project on its project website.

Addressing blended finance’s scaling problem

IFC, which acknowledges its leadership role among DFIs and MDBs in promoting blended finance and chairs a DFI working group on blended concessional finance, has not been immune to accusations that it has used its position to compete with private investors for deals, rather than work with them to mobilise more capital for developing countries.

Ravi Menon, Singapore central bank’s longest-serving chief, suggested a reform of the MDBs’ capital policies in a recent interview, where he was asked about the changes needed to deploy blended finance at scale.

”Today, the MDBs, DFIs and governments do provide financing for the transition effort and decarbonisation, but they are investing directly in projects. In a sense, they are competing with the private sector, because if everyone is going for the commercially viable, bankable projects, who’s going to look at the bulk of the projects which are marginally bankable or below that level?”

By having shareholder member countries of MDBs collectively agree that they are willing to take on more risks, public resources can be better utilised to de-risk investments and crowd in more private capital towards the decarbonisation of hard-to-abate sectors like cement, steel and coal, which typically yield a lower rate of return than investing in renewables.

“This will be one of the major breakthroughs I’m looking forward to in the next one, two or three years because time is running out… But we are not waiting for this. Even as we speak, many of us are having those discussions on how to build financing structures.” said Menon, referencing publications by GFANZ and a blended finance handbook that the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) – a network of over 120 central banks and financial supervisors committed to scaling up green finance which he also chairs – is working on.

Last year, GFANZ issued a statement for the development of G20 country platforms, which are avenues for stakeholders to convene around a specific issue or geography, to coordinate priorities and scale private capital flows towards emerging and developing economies.

In the statement, the coalition encouraged platform participants to work with the private sector to develop a baseline financing roadmap for net-zero aligned development, in order to signal where to focus capital mobilisation efforts across asset classes and investor types.

“This includes setting clear boundaries early in the design of a financing roadmap for where concessional donor funding and quasi-concessional development finance can be most catalytic and where these actors risk crowding out private finance,” GFANZ wrote.

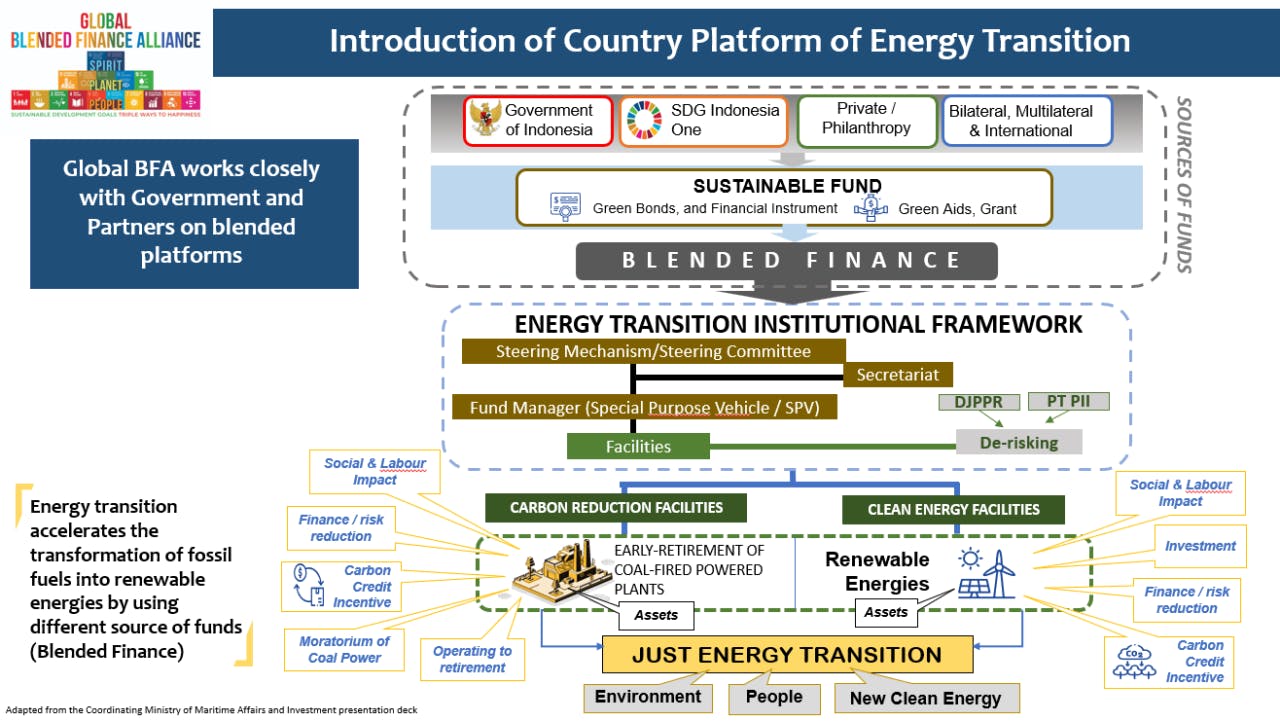

The Global Blended Finance Alliance was launched by the Indonesian G20 presidency and aims to mobilise US$100 billion blended investments for climate action and the SDGs in Indonesia by 2027 by working closely with the government and partners on country platforms, including this one on energy transition. Image: Global Blended Finance Alliance

“Development partners can and should consider where to concentrate public finance resources to achieve maximum impact. Areas like renewables generation, where capacity building and project preparation may be enough to mobilise private sector and investors at scale without the need for further de-risking,” noted GFANZ.

In 2021, the Investor Leadership Network (ILN) and The Rockefeller Foundation penned a Blended Finance Blueprint which proposed seven specific actions the blended finance community can take to reduce risk and increase sustainable investments in emerging economies.

These include creating a rolling pool of funds offering first- or second-loss guarantees so the private sector can cover currently hard-to-insure risks (like regulatory changes, taxation and reputational risks), creating a detailed shared database of projects that MDBs are screening so that private investors can express an interest early on and giving the private sector full access to emerging market risk data and information.

Bae also highlighted the high levels of debt in host countries or companies as a pragmatic factor to consider.

“Most of the blended finance discussions are in the form of debt instruments and with many potential recipient countries having experienced multiple debt crises over the past decades, the structure of these deals, if implemented in the scale that is needed, is going to be an area that needs to be addressed.”

Keen to learn more about the latest trends and developments in the sustainability space? Find out more at Unlocking capital for sustainability, our annual flagship event.