Two of the world’s largest corporate users of plastic, Coca-Cola and Unilever, have said that they’re not convinced by plastic credits as a solution to the marine litter crisis.

Similar in principle to carbon credits, plastic credits allow polluters to offset their plastic footprint by purchasing certificates that represent plastic removed from the environment or recycled.

Russell Mahoney, Coca-Cola’s vice president of public affairs, communications and sustainability for Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific, said at an event last week that the company has explored the viability of plastic credits, but was “not convinced” they’re a suitable solution for a large multinational like Coke.

To continue reading, just sign up – it’s free!

- Get the latest news, jobs, events and more with our Weekly Newsletter delivered to you free.

- Access the largest repository of news and views on sustainability topics.

- You can publish your jobs, events, press releases and research reports here too!

Newsletter subscribers do not necessarily have a website account. Please sign up for free to continue reading!

Coke, which operates in more than 200 markets, aims to “collect and recycle and use again in every market” rather than rely on plastic credits to offset its plastic footprint, he said.

“The idea that you might not do something [collect and recycle] in one market and make up for it in another market is not incredibly attractive to us – certainly not attractive to the people who we might be leaving out as part of that process,” he said.

Mahoney was speaking on a virtual panel at the SEA of Solutions conference hosted by EB Impact, the philanthropic arm of Eco-Business, and the United Nations Environment Programme.

Plastic credits have been dismissed by critics as a way plastic producers can divert attention from meaningful solutions to reduce their plastic footprint. Supporters say they are a valuable tool to channel investment into the underfunded waste sector.

“

We see the things that are working, and the things that aren’t working. I don’t think shutting out anybody [from environmental conferences] is the right way to go.

Russell Mahoney, vice president, public affairs, communications and sustainability, Coca-Cola Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific

Unilever’s perspective on plastic credits is similar to Coke’s, said Vivek Sistla, the company’s regional research and development director, beauty and personal care.

He said plastic credits could potentially work as an extension of an extended producer responsibility (EPR) scheme – where companies are responsible for the plastic they put out into the environment by supporting waste management programmes – but wouldn’t be “at the heart” of Unilever’s plastic management efforts.

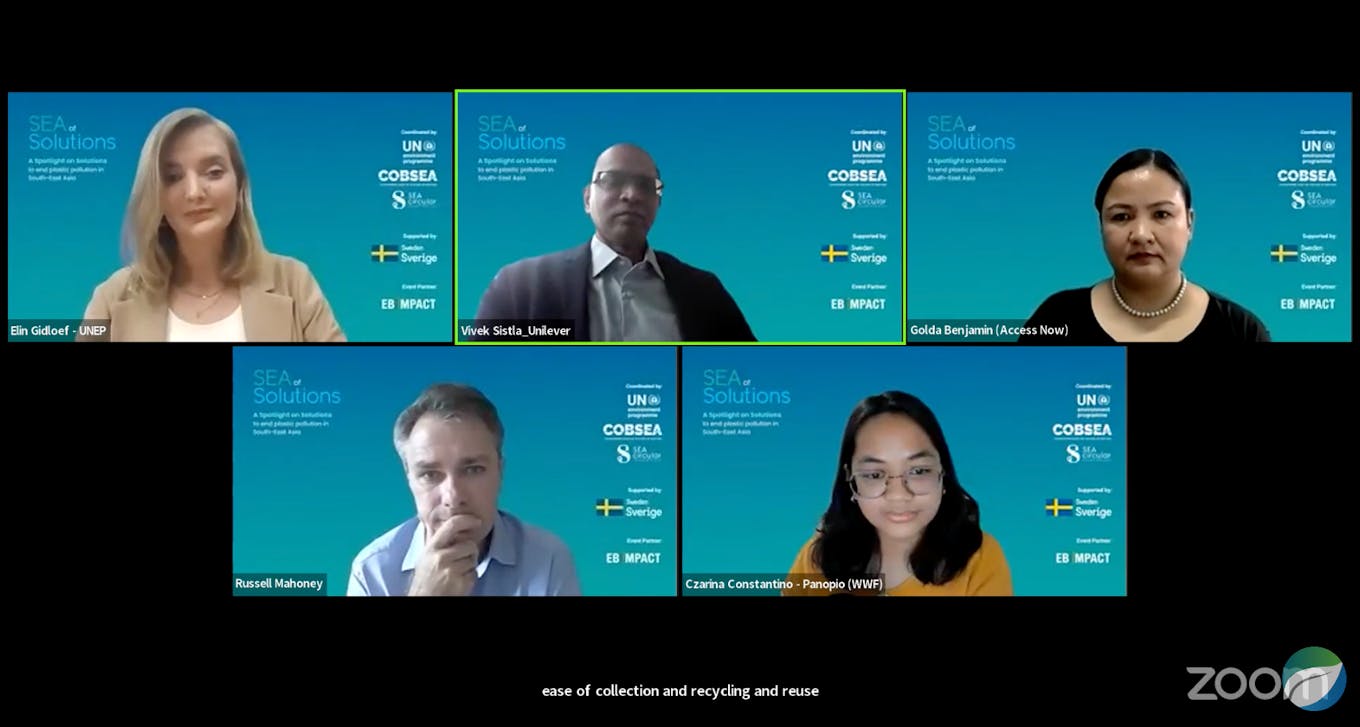

Panelists at the SEA of Solutions event hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme and EB Impact. Clockwise from top-left: Elin Gidloef, UNEP; Vivek Sistla, Unilever; Golda Benjamin, Access Now; Russell Mahoney, Coca-Cola; and Czarina Constantino-Panopio, WWF

Producer responsibility schemes are in the early stages of development in Southeast Asia, and Sistla said Unilever wanted to have “maximum participation” in the creation of such schemes, which he said would help the company work achieve commitments it has set to use “less, better or no” plastic.

Mahoney said governments have the policy levers to drive EPR schemes forward, and these tools were “the hardest and the fastest – [and] more than we can do”. He added that Coca-Cola wanted to be a part of the design and development of EPR schemes.

NGOs have highlighted the environmental impact of brands owned by Unilever and others in studies of litter found in waterways and on beaches. Image: Greenpeace

EPR schemes could play an important role in the creation of a United Nations-led global treaty to prevent and reduce plastic pollution that is slated to be completed by 2024.

Corporate involvement in environmental negotiations

The outsized role that big companies play in climate negotiations and their sponsorship of environmental conferences has raised scrutiny recently.

COP27 was criticised for the heavy presence of fossil fuel interests at the talks. “If you want to address malaria, you don’t invite the mosquitoes,” said Phillip Jakpor, who’s from Nigeria and works for Public Participation Africa, a non-profit.

At a United Nations-organised multi-stakeholder forum on the global plastics treaty on Saturday, non-government organisations from the Break Free From Plastic movement, a collective fighting corporate plastic polluters, said they objected to the presence of companies responsible for plastic pollution.

Christina Dixon, ocean campaign leader at Environmental Investigation Agency, a UK-based non-profit, said: “We cannot allow plastic producers to take control of this process while vulnerable communities struggle with equitable access and having their voices heard in these spaces.”

“We’ve seen yet again challenges with access for this meeting while those companies bankrolling the plastics crisis are able to show up in force,” he said.

Coca-Cola and Unilever are among the world’s biggest plastic polluters, according to data collated of the most commonly littered brands. Both have faced serious public scrutiny for their environmental impact – Coke for its plastic bottles, Unilever for single-use plastic sachets sold in poor countries.

An investigation by Reuters in June found that Unilever has been lobbying against plans to ban plastic sachets in developing countries in Asia, while publicly committing to phase out the packaging, which has had a devastating impact on marine environments in the Global South.

Coke’s sponsorship of the COP27 climate talks earlier this month also drew criticism from environmental non-profits who objected to the “world biggest plastic polluter” using the event to improve its image. A number of NGOs called for the brand to be removed as a sponsor.

Mahoney said Coke “accepted the criticism” and was working towards fixing the company’s plastic footprint with targets including collecting and recycling a bottle or can for every one it sells by 2030 and increasing the volume of recycled plastic it uses in its products.

He said the question of whether large multinationals should take part in environmental conferences was “difficult” but suggested that the answer was “not to shut out a significant portion of the people who can help fix the problem”.

“Companies like Coca-Cola and other large multinationals have to be there listening to the solutions that are being offered. We have to have a seat at the table so that we can offer our experience and expertise,” he said.

“We are fortunate to operate in a lot of markets. We see the things that are working, and the things that aren’t working. I don’t think shutting out anybody, whether it be a multinational or anybody else, is the right way to go.”