There is a growing awareness that the benefits and burden of the energy transition must be equally shared between men and women. In Southeast Asia, with its long-held traditional gender roles and energy inequality, the process is easier said than done.

Big energy developments are on the horizon in the region. Renewables and biofuels are starting to proliferate, while coal is increasingly being shown the exit. Many of these developments will help cut carbon emissions, but a growing body of research suggests that there is no guarantee the benefits and risks can be shared equitably without proper planning.

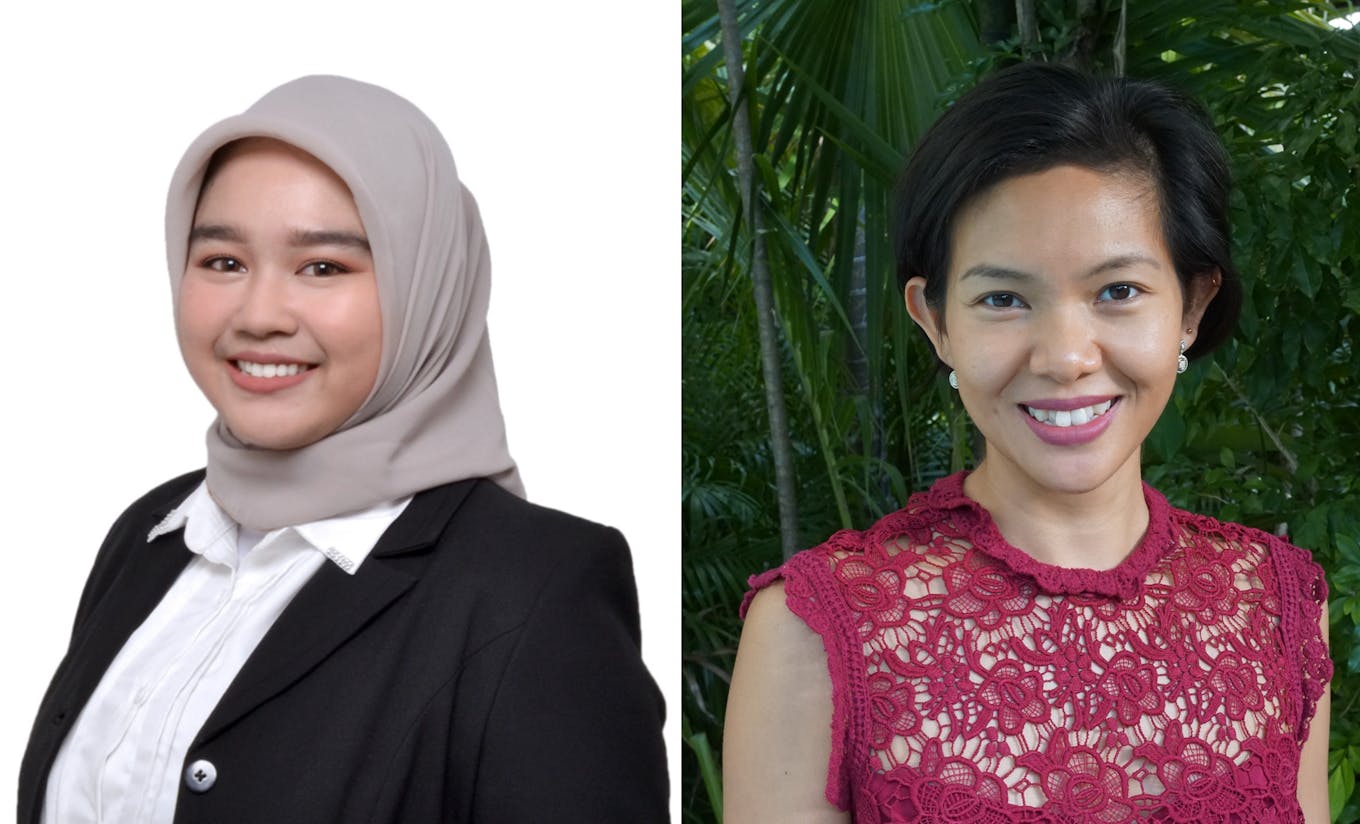

Amira Bilqis (left) is an energy modelling and policy planning associate at the Asean Centre for Energy; May Thazin Aung (right) is a climate change researcher at the International Institute for Environment and Development. Images: Amira Bilqis, May Thazin Aung.

Such rifts could be especially salient along gender lines. Few women work in the energy sector, while their livelihoods are at risk of being upended by big energy projects. The loss of coal sector jobs, held mostly by men, could have profound consequences on gender dynamics in families and societies too.

Joining the Eco-Business podcast to discuss these issues are Amira Bilqis, an energy modelling and policy planning associate at intergovernmental group Asean Centre for Energy, and May Thazin Aung, a climate change researcher at United Kingdom-based think tank International Institute for Environment and Development.

Tune in as we talk about:

- The intersection between gender and energy in Southeast Asia

- The unique challenges impeding progress

- What good governance in energy and gender looks like

- The social risks of coal phase-out

- How stakeholders can chart a viable way forward

This podcast is part of a series on the energy transition in Southeast Asia. Read more stories in our coverage of the topic here.

Edited transcript:

Why is it important to consider the connection between gender and energy transition? What does this look like on the ground in Southeast Asia?

May Thazin Aung: I can talk about the importance of gender in an energy transition in two ways. From a sectoral perspective – I think few people think about this – the energy sector is extremely gendered, from production to distribution to the use of the electricity.

In decision-making, a lot of the technocrats in Southeast Asia are men. They make decisions about where power plants should go, who are the users of energy, who gets to have energy access. Without women’s perspectives in these important decisions, their needs will not be met.

Rural women are still very dependent on firewood. They spend hours of their time out collecting firewood for cooking needs. It creates what we call a “double burden”: women have less time at home if they want to earn an income, but they also need to spend time collecting firewood, cooking, fulfilling domestic duties.

If we envision a future where women are participating as professionals in a low-carbon economy, are they still carrying the double burden of having to cook, collect firewood?

From a holistic societal perspective, I think that a transition in the energy sector is a greater call for justice. It is not just a sectoral issue. How can there be less inequality, and where are women and other members of marginalised groups within our society?

Amira, from your experience working on the RE-Gender Roadmap, how is Southeast Asia faring on gender-aware energy policies?

Amira Bilqis: One thing we firmly believe is that weaving women’s potential into Asean [Association of Southeast Asia Nations] energy dynamics could create positive snowball effects.

Promoting gender equality can also bolster renewable energy investments and accelerate climate mitigation efforts.

In the RE-Gender Roadmap, and another report, the “State of Gender Equality and Climate Change in ASEAN”, we found an alarming gender inequality in the energy sector, which is dominated by fossil fuels and relies on dirty cooking fuels that put women’s health at disproportionate risk – they are the major domestic energy consumers.

Moreover, women’s employment rate in the energy sector is only 8 per cent, which is insane to think about, because it means very few women benefit from working in this industry.

In another study the Asean Centre for Energy conducted on gender, energy and development finance, we found that the region only received 6.2 per cent of US$11.4 billion spent globally on energy and gender programmes. The report showed that projects with gender objectives will increase visibility with donor countries’ development assistance strategies. So if we add gender considerations to energy projects, we could better secure funds for the energy transition.

Right now, we have a breakthrough in the RE-Gender Roadmap, aimed at charting a path to accelerate renewable energy development in Asean. This roadmap is the first of its kind here.

That’s interesting. What specifically do donors ask for in terms of gender considerations? And also, it has been about half a year since the RE-Gender roadmap launched. How much progress has been made since?

Amira Bilqis: This roadmap stems from a statement by the Asean member states during the 39th Asean ministers on energy meeting in 2021. Asean Centre for Energy then teamed up with EmPower [a gender equality project], implemented by the United Nations Environment Programme, and UN Women.

There isn’t much of a very specific numerical target, because what we have are very preparatory measures, it is to pique the political will and interest of policymakers, and to inform us of the potential collaborations with other countries, partners or international organisations which have a better understanding of these issues.

One thing I’d like to highlight is it was a bit challenging engaging policymakers in the development of these tools. The team received limited responses at the data collection stage, even after conducting webinars and focus group discussions with them. I would say that the awareness of the representatives from Asean member states remains limited. Not everyone, but there are some countries – probably because their representatives are from an energy background with a limited exposure to how energy intersects with gender.

Convincing policymakers themselves to take this unusual step requires a strategic approach – we are doing our best to emphasise the benefits of integrating gender into energy policy and planning.

This year, the Asean energy blueprint, APAEC, will undergo a mid-term review. If we can take this opportunity to firm up the member states’ political will. Next year, Asean will start developing the next phase of APAEC, for 2026-2035 – which is a golden opportunity for gender-aware energy policies.

How unique are the challenges that Southeast Asia faces in incorporating gender considerations into energy policies? May, I recall you touched upon biofuel plantations and hydropower projects in your research here.

May Thazin Aung: The situation is unique in Southeast Asia for a couple of reasons. Decision-makers are technocrats, not only are women not included but also they lack the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics skills needed. That is an educational problem.

There are gender norms as well, like engineers being seen as masculine professions, as well as patriarchal structures in place. For example, Indonesia’s fossil fuel sector has a very tight-knit group of political elite. So if we’re trying to envision a new pathway where renewables are predominant and women have a say in decision making, we really have to break down some of these strong patriarchies.

There are also practices that are potentially unique to Southeast Asia, on meaningful consultations with communities in the decision-making around where hydropower plants and oil palm plantations go. Women often are not sufficiently consulted because they do not have secure land tenure, usually the land is in their husbands’ names.

So women do not benefit from compensation, they suffer from displacement and gender-based violence from these large-scale infrastructure projects.

I’d also like to add that a big thing to question in Southeast Asia as a part of this transition is whether we have sufficient systems of welfare to enable women to access professional careers? Are we going to have scholarships and training programmes targeted towards women so that they can be decision-makers and leaders in a low carbon economy?

So what does good governance look like? What needs to change?

Amira Bilqis: At the regional level, we need to place a gender specialist at the heart of agencies like the Asean Centre for Energy. That is the first thing to do.

Second, Asean policymaking processes need advisory groups to help with cross-sectoral, multi-level issues. They can help gain insights from the grassroots level too.

The RE-Gender Roadmap states that policymakers should have very specific gender working groups, incorporating energy and gender experts, local communities, companies, universities and international institutions, to help with gender mainstreaming efforts, as well as monitoring, reviewing and planning the way forward.

Gender mainstreaming efforts need to be sustained, reviewed, monitored at every level, every year.

Some countries may feel that establishing a new department needs additional budget and they don’t opt for that because they feel there would be no immediate return. But there are other approaches.

For example, in the Philippines, the Department of Energy is equipped with a gender toolkit and gender development focal point system, with guidance from the Philippine Commission on Women. The focal point itself consists of an executive committee, technical working group, secretariat, implementors, even monitoring systems. You can see that it is a complex group that engages every high-level position.

They are responsible for mainstreaming gender across energy policies, and setting up mechanisms for collecting and processing sex-disaggregated data.

Other Asean member states could replicate these best practices and tailor that to their needs and budgets.

One of the things we could even envision is to have renewable energy projects led by women. They are energy managers and consumers who understand better the needs of their communities. At the same time, it’d be great if they are given a safe space to represent women’s interest in the energy sector. As I mentioned, advisory groups, working groups.

May Thazin Aung: I would just add a few more things. I’d like to call attention to the importance of establishing clear processes for communities to be involved. This should be transparent and public to ensure that communities, women’s groups, other actors like small and medium-sized businesses that are women owned, can be involved in the process.

There should be systems of accountability, maybe in the form of community monitoring where people can text in when they see commitments the government has not followed through with.

On energy policy, yes we need gender audits, to ensure that disaggregated impacts can be understood. For example, there are studies that show that without proper understanding of energy use and needs, female head of households would be the last to be connected to an energy grid.

In Southeast Asia, we have lots of different types of energy uses by women. There are people on the street selling food, there are small businesses on carts. Their energy needs would be different than when they are at home.

Both of you mentioned a lack of data, and persistent perceptions and dynamics on gender, as two main challenges. Which is the greater obstacle to progress?

Amira Bilqis: We identified a lot of challenges in the RE-Gender roadmap. But one of the core issues that I think will have ripple effects is really the lack of data on gender and energy. How can we solve problems if we don’t even understand them? We understand them in a general sense, but again the details are not visible yet, we still have very limited data collection capabilities on sex-disaggregated data. Policymakers need evidence, data and models.

So building the region’s capacity to enrich its gender data on energy would help. Asean actually has a lot of platforms, we have the Asean Energy Database System, to support any related gender data. But if we can complement that with something more than just focusing on technology and projections of investments et cetera, towards a more social approach, then it would help policymakers gain a better understanding of the issues.

Gender data and benefits sometimes are not easily countable, unlike almost any other energy statistics. So we are calling for external parties to support us technically and financially, to improve such data capacities.

May Thazin Aung: I agree, but I also see it as a two-fold issue. Data is really important and we’re unable to understand what the issues are if we don’t have the data, but there could be reasons why the data is not collected.

First, it is a perception issue. Gender is not important, so why should we collect data on this that can be?

Also, the lack of data could also be due to a lack of strong research institutions, or that decisionmakers are not valuing the importance of research enough. There are strong research institutions in Singapore, but in my country Myanmar, the education system is very lackluster.

There has been research on how coal phaseout affects gender power balance in the United States and UK, where the transition started years earlier. Women did benefit from some trends like going to work as men lost their coal sector jobs, but there were also accounts of more vice and violence from the men. How applicable are such studies to Southeast Asia now?

May Thazin Aung: There is a lot to learn from that. You already mentioned that there will be impacts when gender roles change between men and women. And there could be consequences for women as a result, because men feel that their masculinity has been taken away, they lost their jobs as coal miners, as breadwinners for their families.

That is something we can learn in Southeast Asia as well, that when we decarbonise, the role of women is going to change. When women have better education, when their roles in households change, there will be systems of power that are not used to women having a new voice and role as income-earners.

We need to plan for this. It could take the form of protections to make sure that women don’t suffer from gender-based violence at home when there is a rebalancing of power asymmetries. It could be making sure that women can take up meaningful jobs.

In the US, UK coal transitions, women became income earners when men lost their jobs, but the women got poor quality jobs. They were in administrative, part-time roles, not professional ones.

I think we already see this in Southeast Asia. The 8 per cent of women employees in the energy sector that Amira mentioned – many of them will be in an administrative role, in human resource, not in leadership and technical roles.

It is very much about better education, vocational training, and systems of support that we mentioned – equal pay, family benefits, good quality leave for maternity.

Another important thing is the psychological impacts of change, of losing jobs and the rebalancing of power asymmetries. This has psychological impacts on people, so mental health and well-being should also be emphasized.

Amira Bilqis: The research is very relevant to us, it it might be something that happens in the next decade or so in the region, when coal is phased down and new renewables jobs are created. We see this as a projection that is realistic.

But there aren’t dedicated studies on this in Asean. Hopefully the UK-US study can trigger research to elaborate and explore such issues, including comparative studies.

That paper can be seen as a warning to this region’s policymakers to provide tailored, preventive measures, to cushion the effects of the coal transition on women, and to empower them to participate actively in the transition.

May Thazin Aung: I just want to add one more thing that I think is really important. The UK-US studies showed that the effects of a coal transition are societal. They’re not just limited to the household level, so that is something I hope Southeast Asia takes into consideration.

In our countries, it is not just about the miners, it is about the communities of people revolving their lvies around the industry – people selling food to miners, tuk tuk drivers transporting the goods…that is why it is important to understand the community-level impacts, and the impacts to informal workers.

Overall, do you think the solutions lie in simple fixes with big impacts, or system change?

Amira Bilqis: We already have so many issues in the energy sector, and now if we want to bring it to a whole new level of understanding of the social impacts, I think I lean towards a need for systemic change.

As I mentioned, the inclusion of gender issues in APAEC would help firm up political will of Asean member states. It is a needed milestone on how the region reacts to gender and energy issues.

The next stage should be on designing policy, understanding frameworks, having a gender-responsive budget and financial framework, and having a monitoring and evaluation system. We need new working groups, advisory groups and supporting infrastructure. It amounts to systemic change.

May Thazin Aung: I think systematic change systemic change is necessary to transition to a future where marginalised people are included in decision making. It is about dismantling the power structures that are in place that characterize the current fossil fuel economy, and making sure inequalities and inequities are addressed. These are big questions.

But I also strongly believe that small-scale solutions have an impact. For example, it is important for us to share our perspectives in conversations like this. It is important to go home, talk to our families about the role of women in society. It is about beginning to take steps to change the gender norms that characterise our society.

Amira Bilqis: One of the shortest-term changes I’d like to see is for us to talk about gender and energy all year long, not just in March because of International Women’s Day. We need it as a priority across the years.