In its fight against climate change, Southeast Asia has been warring with a new enemy – methane.

A greenhouse gas, methane traps more heat in the atmosphere and is over 80 times more effective in heating the Earth compared to carbon dioxide when measured over a span of two decades.

Roughly 10.5 per cent of methane leaks and emissions in Southeast Asia comes from its oil and gas industry, according to an estimate by researchers at Singapore think tank ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

While there are relatively low-cost opportunities abound to plug methane leaks from this sector, lax regulations, low awareness and conflicting investment priorities stand in the way.

The region, home to several fast-developing economies, is a producer and growing user of petroleum and natural gas. Researchers from non-profit Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and regional think tank Asean Centre for Energy say governments should set rules for monitoring and capping methane emissions to compel businesses to adopt solutions already viable in the market.

Against growing odds that the planet will remain within the 1.5°C safety limit for global warming this decade, policymakers are realising that a quick respite is possible if methane leaks are sealed fast.

Such an effort is especially important for Southeast Asia’s energy sector, since oil and gas “are and will remain the backbone of the energy supply” in the region, said Beni Suryadi, head of the power, fossil fuel, alternative energy and storage department at regional think tank Asean Centre for Energy.

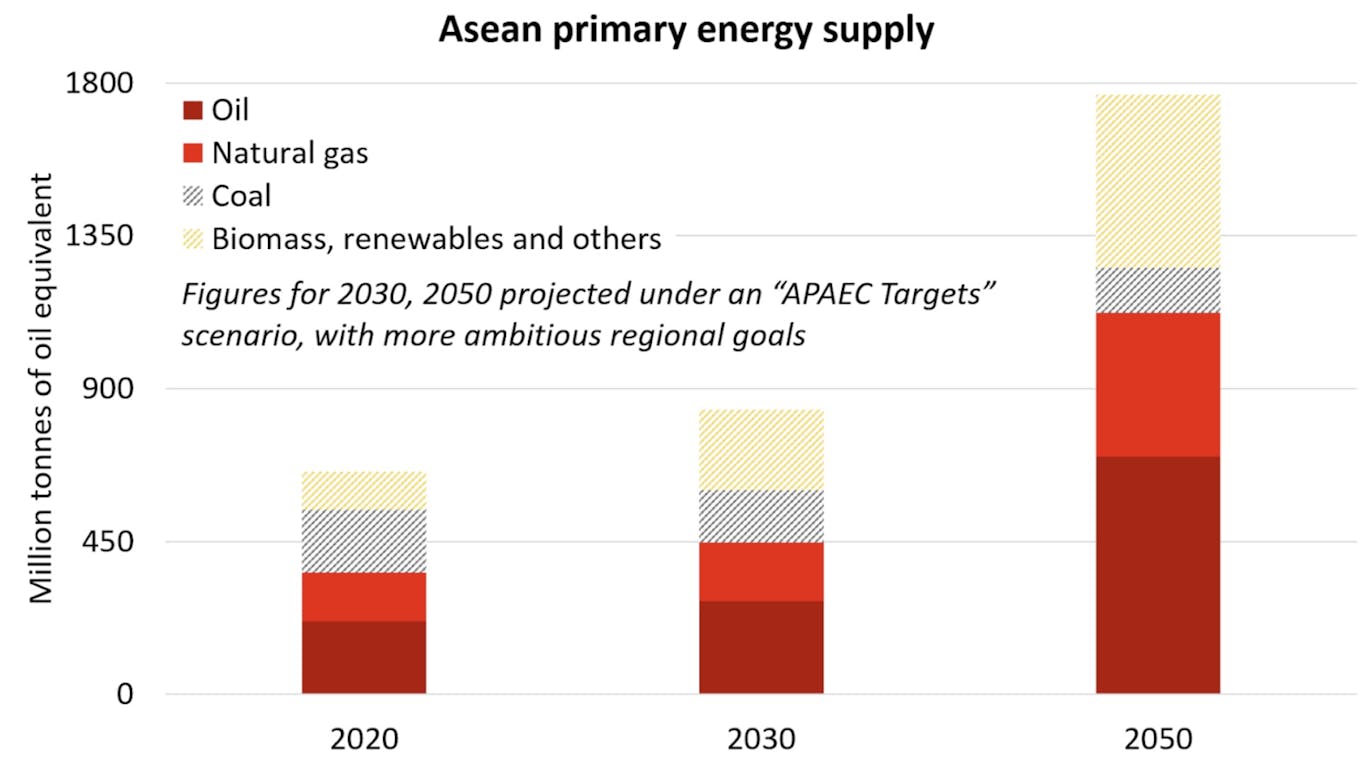

The centre, whose research covers the energy interests of member countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), has projected that oil and gas will still contribute over 60 per cent of the region’s primary energy supply in 2050, even if Asean increases its reliance on renewables.

The total energy derived from oil and gas will essentially triple from today since fuel and electricity demand from factories, households and car owners is expected to skyrocket in the rapidly-developing region.

Oil and gas needs in the Asean region are expected to triple by 2050, even if more ambitious regional goals are pursued. Data: Asean Centre for Energy.

Suryadi noted that there are workable and cost-effective measures to help oil and gas players reduce methane emissions. This includes stemming leaks, cutting back on gas venting and flaring, and using clean electricity for industry operations.

In fact, cutting methane emissions from the oil and gas sector is touted as a climate fix that would quickly pay for itself. Methane is the main component in natural gas, and fewer leaks would mean increased gas sales and higher profits. The International Energy Agency estimates that 40 per cent of methane emissions from the industry – or 10 per cent from all human sources – could be abated at no net cost.

Southeast Asian energy companies, including several large state-owned enterprises, are only starting to recognise the importance and business benefits of such sustainability efforts, said Dr Shareen Yawanarajah, director of global energy transition at EDF.

“Many of the national oil companies have to start at training and education because it is a new topic for staff and also for the energy and environment ministries,” she said.

“That is really the first step because it is very difficult to get decision-makers to agree on any kind of corporate action before they actually understand [its necessity],” she added.

But conflicting investment priorities against other business ventures, such as exploring new fuel deposits, is the “biggest challenge” in getting initiatives off the ground, Yawanarajah said, noting that state-owned companies, which receive funding from governments also compete with funding needs in the country.

While countries like Japan and South Korea have pledged support for methane reduction activities in Asia, Yawanarajah said financing mechanisms remain “very opaque”, making it difficult to get public sector finance approved for specific projects. EDF is currently working on a policy paper on unlocking funding for methane reduction efforts in the region.

Suryadi said some technologies need significant upfront investments, making it challenging for some companies to justify the purchases in the short term. Advanced tools used in the oil and gas industry include drones, aircraft-mounted sensors and satellite imagery.

Tools to fight methane

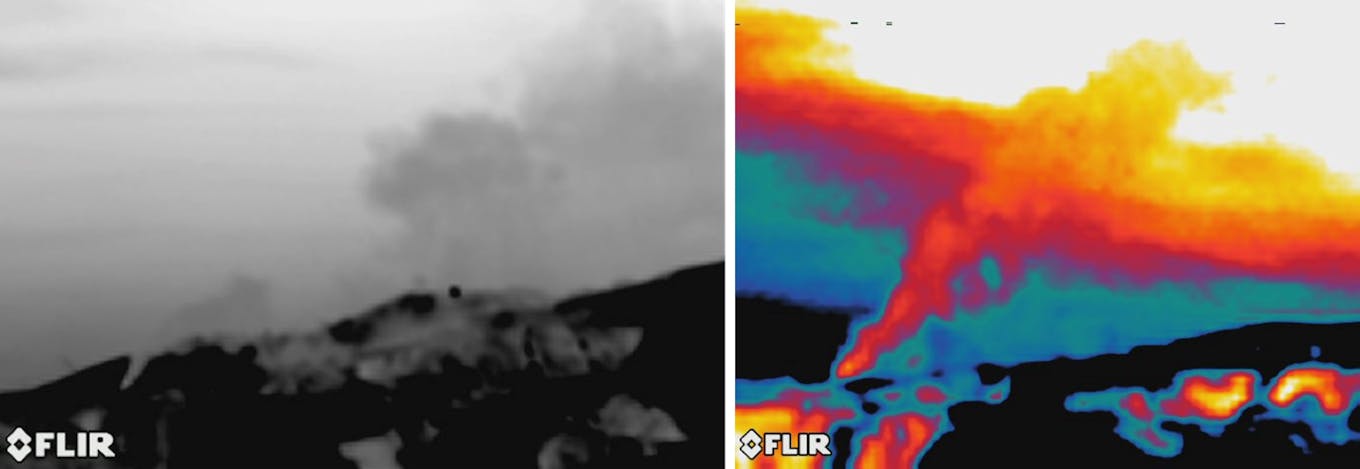

In the 1980s, gas workers needed six months to manually check pipes and valves at gas processing plants for methane leaks. Today, with infrared cameras, the entire exercise can be completed in two weeks, according to Teerasan Koolmongkolrat, an engineering executive from Thailand’s state-owned oil and gas company PTT.

The cameras would be used for broad sweeps before other equipment is brought in to analyse and fix the leaks, Koolmongkolrat shared at a regional methane workshop hosted by the United States’ Agency for International Development (USAid) in December 2022.

Such tools to identify accidental venting and allow for speedy repair work could help address a sizable portion of methane leaks. Indonesia’s state-owned oil and gas giant Pertamina identified leakage as the primary source of methane, accounting for 50 per cent of the total emissions, according to its executives who presented at the USAid workshop.

Suripno Suripno, a senior official for health, safety, security and environment at Pertamina, said that methane abatement is a “low-hanging fruit” and a “no-regret” move for the company, as lower leaks reduce fire and explosion risks, on top of the revenue savings and climate benefits.

Infrared cameras picking up a methane plume in California, United States. Images: Environmental Defense Fund.

Suryadi said tools to quantify methane emissions are also among the most needed technologies for energy players in the region, since quality data is needed to craft mitigation strategies and build trust with stakeholders through sustainability reporting.

Whereas such emission calculations had been tabletop exercises involving rough estimations over businesses’ entire operations, the industry is moving towards the use of digital sensors and even laser-based instruments to quantify emissions, though the higher costs could deter adoption.

Drone and satellite-based gadgets, meanwhile, come with their own limitations. At the USAid workshop, Aidi Wan Zakaria, an instrument staff engineer at Malaysian national energy company Petronas, noted that strong winds can impact a drone’s ability to pinpoint sources of methane emissions, while cloudy conditions could affect satellite measurements.

In addition to leaks, methane is also frequently expelled via deliberate venting and burning when fuel companies release excess supply that cannot be sold, typically due to cost issues or as part of regular maintenance procedures.

Flaring and venting from hydrocarbon production are the main sources of methane emissions at Petronas, the company’s chief sustainability officer Charlotte Wolff-Bye told Eco-Business. Efforts to reduce such activities in 2021 saved nearly 134,400 tonnes of methane from being emitted, and Petronas aims to report flaring data annually starting this year, Wolff-Bye said.

Finding viable and economical ways to reduce methane emissions from oil fields with small or intermittent gas reserves remains the biggest challenge facing Petronas, Wolff-Bye added.

The company reported a 48 per cent drop in its methane emissions to about 215,000 tonnes between 2019 and 2022 in its latest annual report. But it is also looking to expand its extraction activities, with 10 new offshore discoveries made in 2022.

Dr Mark Lunt, a methane scientist at the EDF, said companies can consider applying improved technology to increase the combustion efficiency of flares or finding alternative uses for the spare gas. For instance, the United States government has been studying the use of surplus methane for making novel fuels such as hydrogen and ammonia, or solid carbon, which can be used as industrial feedstock.

Lunt noted that although oil and gas contribute fewer methane emissions than farming globally, at 25 per cent against 40 per cent, solutions are more readily available for the fossil fuel sector. In the food space, experts are grappling with cutting emissions from rice fields and livestock – both of which present no easy fixes.

“Reducing methane emissions from the oil and gas sector is both technically and economically feasible, which is why it is such a focal point,” he said.

Lagging laws

Experts say stricter laws in Southeast Asia will be needed to speed up methane abatement among energy companies.

“Many countries in Asean do not have regulations in place to monitor and control methane emissions [in the oil and gas sector], or their existing regulations may not be adequately enforced,” said Asean Centre for Energy’s Suryadi.

There has, however, been some progress. Thailand has emissions standards for volatile organic compounds – or gases that evaporate easily at room temperature such as methane – from oil depots. Vietnam has said it will develop policies to encourage businesses to trap effluent gas from oil extraction and invest in leak detection equipment. Vietnam is among six Asean countries – along with Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Singapore – that are signatories of the Global Methane Pledge, which is a commitment made by 150 countries to slash methane output by 30 per cent this decade.

But countries in the west are moving faster.

The United States started taxing methane emissions from the oil and gas sector through its landmark climate bill, the Inflation Reduction Act, passed in 2022. It has also set a target to lose no more than 0.2 per cent of all methane extracted before the gas reaches customers.

The European Union is finalising laws that would mandate more stringent monitoring and leak detection for methane emissions in the energy sector, and impose such requirements on fuel imports.

“Then the question [for Southeast Asia nations] becomes: do you want to pay the [import] tax and have the money go to the EU, or do you want to apply something similar internally and keep the money in the country?,” said EDF’s Yawanarajah.

Nonetheless, Yawanarajah noted that voluntary corporate action is on the rise in Southeast Asia. Petronas leads the pack, she said, being the only Southeast Asia company signed on to the United Nations’ “Oil & Gas Methane Partnership 2.0”, a reporting framework requiring oil and gas companies to set methane reduction targets and report on their progress.

Petronas has said it would halve emissions by 2025, and reduce it further to 70 per cent by 2030.

State-owned companies such as Petronas, Pertamina and PTT have also set 2050 net zero targets, albeit for internal operations only.

Experts say regulations in Southeast Asia should be developed stepwise. Suryadi said there needs to be studies on how companies can comply with regulations while leveraging new opportunities to be more efficient. Yawanarajah added that well-developed regulations can also spur new industries that offer decarbonisation opportunities while offering more jobs.

Still, there are strong voices globally calling for oil and gas activities to be halted entirely, instead of just being decarbonised.

Each country would need to reconcile its energy and climate policies, Yawanarajah said, but with major fuel-producing countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia having set net-zero emissions goals for 2060 and 2050 respectively, she noted that reducing methane should be the “first step in any decarbonisation goal” in the oil and gas sector.

She added she does not believe methane reduction efforts will prolong fuel companies’ activities in traditional oil and gas development, given their awareness today of the need to shift to lower-carbon products.

“With increased pressure from shareholders and from the grassroots level, [oil and gas companies] are no longer able to run their operations behind an opaque curtain,” Yawanarajah said.