From the small window of the propeller plane where I sat in freezing temperatures, the landscape that greeted me below seared into my memory. A modern-day Mordor — barren, charred, marked with pools of murky water as far as my eye could see, with miniature steel structures, oil rigs, smoke chimneys, and Caterpillar trucks providing specks of colour.

It was 2008. I was flying into Fort McMurray, in Alberta, Canada, where in the past few decades the country’s boreal forests have made way for the controversial oil sands industry. I was a young journalist then covering the energy beat, and I was invited by Shell to visit their operations.

The Athabasca oil sands, also known as tar sands, are home to the largest deposits of heavy crude oil in the world and because it exists in a mixture of bitumen, sand, clay minerals and water, it is expensive and dirty to extract.

Billed as the world’s dirtiest fuel due to its ecological impact and high emissions, the industry’s growth had been driven in the aftermath of the 1970s oil crisis and amid energy security concerns. As I interviewed the workers and surveyed the operations on the ground, it was clear the industry provided a key source of livelihoods for locals — for many, never mind the high-profile environmental protests, it was even a source of pride.

By opening its operations to journalists then, Shell wanted to demonstrate how it extracted this fuel in a responsible manner. While I was persuaded of the high standards of safety and worker welfare, that entire experience — from feeling the tension between communities, understanding the trade-offs involved, and witnessing the devastated landscape — became for me a deeply-imprinted manifestation of the unprecedented impact that humans have on the planet.

That assignment formed part of a special report I eventually wrote for The Straits Times. Headlined “The heat is on: Once the domain of dreamers, the development of clean, green energy is now more critical than ever”, it investigated the changing forces shaping our energy systems. I became hooked on the topic, writing stories exploring the relationship between business and our natural world whenever my editors would let me.

The era we live in now has been termed by scientists as the Anthropocene, in which humans have become the dominant force shaping Earth’s bio-geophysical composition and processes, including climate change and its consequences such as sea level rise, extreme weather events, the effects of plastic pollution on marine and terrestrial processes, unprecedented rates of biodiversity loss and extinction, and the changing chemical composition of soils, oceans, and the atmosphere.

As I reflected on how the Industrial Revolution has yielded cheap and abundant energy driven by the mass extraction and burning of fossil fuels — and in turn fuelling the rise of capitalism — it became crystal clear that we were only starting to comprehend its extraordinary impact on the planet and our ecosystems, and that we desperately needed to find new ways of sustaining humanity.

Within the year, with the blessings of my editors, I started cooking a first-of-its-kind news platform that would allow journalists to write and publish stories on these complex issues. I was grateful for the initial seed funding provided by the British High Commission and the Singapore Environment Council then, and with a loan from my mother, Eco-Business was launched in November 2009 just prior to the landmark United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) meeting, or COP15, in Copenhagen, Denmark.

*

People often ask me about the inspiration for Eco-Business’s name, and many assume it simply means “eco” as in “environment” and “business”. In fact, the name is the combination of “ecology” and “business”. Looking at the etymology, “ecology” is a term derived from Greek, meaning learning about “logos” or the ecosystems, while “eco” comes from the Greek word “oikos”, meaning “household”.

In other words, ecology is the study of the relationships among living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment, at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Eco-Business was set up to investigate the interactions of our ecosystems with one another, and it is still the north star that guides the company’s coverage, advocacy and thought leadership activities throughout the region.

It was extremely tough in the early years to gain traction, as few really understood what we were trying to do. In more than a decade since, it has been gratifying to see the issues that we cover now at the top of international agendas and being debated extensively.

Sadly, it is also due to the fact that the climate crisis has made its presence felt more acutely across the world. But encouragingly, global attention on this issue has gained momentum and in 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to provide a framework for humanity’s development that looks after that of future generations. Later that year, 196 nations under the UN adopted the Paris Agreement, which, for the first time, provided a global treaty to address climate change.

“

People often ask me about the inspiration for Eco-Business’s name, and many assume it simply means “eco” as in “environment” and “business”.

In fact, the name is the combination of “ecology” and “business”. Looking at the etymology, “ecology” is a term derived from Greek, meaning learning about “logos” or the ecosystems, while “eco” comes from the Greek word “oikos”, meaning “household”.

Eco-Business has since grown from a small Singaporean operation to have a presence in the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Hong Kong, China and India, and hopefully even more countries in the future. Every single day, the issues we cover continue to fascinate me. This complex relationship between the role of business and our ecology deserves our attention, and we need to have informed debates and constructive dialogue with each other to chart a way forward that continuously improves how we live.

*

Some years after Eco-Business was launched, I was invited to author a book to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the then-Ministry of Environment and Water Resources (MEWR) in 2012 and more broadly, Singapore’s environmental journey. Published by Straits Times Press, the result of that effort, Forging a Greener Tomorrow: Singapore’s Journey from Slum to Eco-city, for the first time dived into the archives to document Singapore’s environmental challenges during its pre-independence days and its subsequent journey over the decades.

I was grateful for that endeavour, which provided valuable access to former ministers, permanent secretaries, agency CEOs, rank and file officers and a diverse set of stakeholders including UN officials. I interviewed more than 100 people for the book and these interviews provided me with rich history lessons on the twists and turns in the journey of a young nation state in seeking independence, economic success and long-term sustainability.

As I wrote then, many today will look back on Singapore’s early post- independence kampung days with nostalgia and memories of a simpler village life. But those living in the 50s and 60s will also recall how water supply was frequently disrupted, toilets were outdoor huts with a hole in the ground that housed a night soil bucket, streets were choked with rubbish and Singapore’s waterways were open sewers. While these days we worry about the next unknown virus that could cause a pandemic, back then it was the fear of catching mundane diseases such as typhoid, malaria and cholera.

In a few short decades, Singapore has earned an international reputation for its innovation in water recycling, and as a clean and green city — it was a vision articulated by Singapore’s founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, who declared in his memoir From Third World to First: 1965–2000: “After independence, I searched for some dramatic way to distinguish ourselves from the other Third World countries. I settled for a clean and green Singapore.”

Former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong once joked that Singapore’s cabinet must be the only one in the world that read the minutes of a garden city committee.

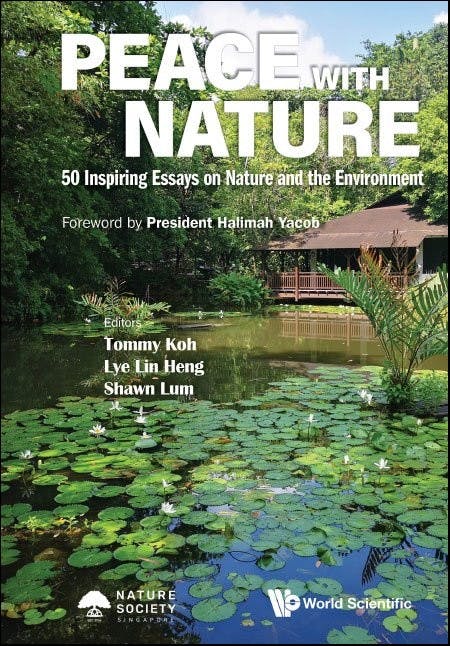

Peace with nature, a compilation of 50 essays written by Singaporeans and friends who share their perspectives, expertise and experience - as scientists, lawyers, economists, engineers, bankers, government officers, and civil society - all linked by a love for nature, for the environment, and for Singapore. Image: World Scientific

The journey to where we are today was however not without plenty of sacrifices and trade-offs where nature is concerned. While the island’s green cover has been increasing to over 40% according to latest figures, only 0.3% of an island once entirely forested is now classified as primary forest. As Singapore’s natural landscapes made way for gleaming skyscrapers, industrial buildings and public housing projects over the decades, there were some small conservation victories. Some examples of rare policy reversals include the preservation of Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve in 1986, Lower Peirce Reservoir in 1992, and Chek Jawa in Pulau Ubin in 2001.

Meanwhile, ongoing development chips away at the edges of what remains. Perhaps one silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic was that, when millions of residents on the tiny island became involuntarily trapped, it catapulted into Singapore’s collective consciousness the value of nature and open spaces.

The pandemic prompted a quadrupling of visitors to Singapore’s nature parks and some environmentalists commented on how visiting Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve for a bird-spotting competition gave them the feeling of being in “just another crowded shopping mall”. While there was visible concern on the impact of the overwhelming visits, there was also hope that Singapore’s renewed appreciation for nature would continue to be preserved in the future.

In 2021, increasingly nature-conscious citizens were up in arms when a developer flattened a piece of woodland in Kranji that it was not meant to. Photographs juxtaposing Singapore’s historical railway flanked with luscious green woodland against those of the cleared, barren land shocked the public. The incident triggered an ongoing criminal investigation. These acute tensions between nature and development, citizens and government are still playing out today in the debates around the Cross Island Line, which will controversially run directly under Singapore’s largest nature reserve, and in the debates on how much of Dover Forest should be left alone.

*

It has been a decade since that book was published. MEWR has now been renamed the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment as a reflection of the times, and Singapore has had to confront a different set of challenges. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in his milestone 2019 National Day Rally identified climate change — for the first time — as an existential “life and death matter” for Singapore, pledging S$100 billion to shore up our defences. The country has since declared a net zero target by 2050 and launched the Singapore Green Plan, an updated national blueprint to guide our sustainable development journey.

There have been a few hits and misses along the way. We missed the opportunity to electrify our transport systems earlier — despite Singapore’s ideal small size and tech-savviness, it took more than 10 years of being in what I term “perpetual pilot mode” before regulators made the call to support this shift; Singapore’s resource consumption rates, along with its carbon footprint per capita are among the highest in the world, while its recycling rates remain abysmal despite repeated national campaigns.

But Singapore has also shown leadership in being the first Southeast Asian country to declare a carbon tax; its regulations are among the highest in environmental standards, and there is a recent palpable momentum in building a resilient, competitive green economy, including fostering renewable energy trading, carbon services and sustainable finance activities in the region.

While the government provides the legislative framework and national budgets to spur the transformation needed to achieve the Paris Agreement and SDG targets, businesses play an even more critical role. They have an outsized footprint on our ecology, yet often overlook the fact that nature provides services worth at least US$125 trillion per year globally, providing all that we need and facilitating global trade and livelihoods for billions of people. It seems that we are, as UN Secretary-General António Guterres said recently, “waging a self-defeating war on nature”.

“

Will we see such a conversation in Singapore? It is my hope that the next generation of leaders will put this on our national agenda.

The fundamental role of business has been the subject of a lot of recent debate. It has been three centuries since Adam Smith’s 1776 book, The Wealth of Nations, defined gross domestic product (GDP) — the monetary value of final goods and services produced in a country in a given period of time — and provided the foundation for classical economics and capitalism. Milton Friedman went on to popularise the doctrine that the social responsibility of business is solely to increase its profits.

These definitions are outdated. We urgently need to redefine them and create a new set of metrics that are fit for purpose in this century. Encouraging conversations are happening, such as the rise of “stakeholder capitalism”, which prioritises all stakeholders rather than only shareholders, and the increasing global importance of environmental, social and governance (ESG) strategies in investment decisions. The latter movement was borne of a seminal report Who Cares Wins in 2004 led by the late then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan to better integrate ESG considerations into finance.

Other promising signs include the European Parliament’s Beyond Growth 2023 forum which is aimed at “challenging conventional policy-making in the European Union and to redefine societal goals across the board”. Will we see such a conversation in Singapore? It is my hope that the next generation of leaders will put this on our national agenda.

Meanwhile, my work continues to take me to far-flung corners of the globe. From the Antarctic to the Arctic, the Himalayas to the Sundarbans, my mission on every journey has been to document the wonder of our natural world, to explore the impact of humanity and to provoke awareness and action. Antarctica was a particularly unforgettable realm — it is the only place on Earth relatively untouched by man, thanks to a global treaty (which is to be reviewed in 2041) that preserves it for science and peace. The scale of its mountain ranges, glaciers, wildlife, and its all-encompassing sublime beauty makes you feel simultaneously inspired and in awe, yet acutely insignificant and ephemeral.

I yearn for and chase experiences with these majestic natural landscapes. That adage “you can’t protect what you don’t know” rings true. At the same time, I have realised while we have witnessed unprecedented biodiversity loss and the degradation of natural ecosystems, fixing climate change and all the ills of not living within our planetary boundaries is more about ensuring our own survival. Nature will march on its timeless, relentless path — whether humans survive or not.

At home, on this little red dot, I seek the pockets of nature that provide a healing and thinking space whenever I can. There are many if you look for them. I intentionally live next to a forest on a hill with a road flanked by luscious trees — here we encounter monkeys, bats, snakes, and all sorts of wildlife which provides learning opportunities for my kids on the nature that is at our doorstep. Four nature parks surround us, and we seek out Singapore’s coastal parks on weekends too, for that wide horizon and calming presence of the repeated ocean waves lapping onto its shores.

These days, the sight that greets me from an airplane window whenever I return home is an expanse of the Singapore Straits dotted with vessels, trees hugging the coastline against blocks of flats, and reclamation and construction works. Wherever we cast our eyes, there are splashes of green. As our country continues to evolve, it is my hope that we will always remember this of nature — we can never have enough of it.

*

This essay is Chapter 4 of ‘Peace with Nature: 50 inspiring essays on nature and the environment’ published by World Scientific and edited by Tommy Koh (Ambassador-at-Large, Singapore)Lin Heng Lye (National University of Singapore)Shawn Lum (Nature Society Singapore). Publishers have an ongoing discount 20% off from now to 31st October 2023. Please use the Code WSASOC20.