Indonesian voters are gearing up to elect their next president on Valentine’s Day 2024. While Indonesia is still enjoying resilient economic growth, its long-term prospects are not as rosy as it may seem. Immediate policy action is direly required to address long-term developmental challenges as Indonesia’s demographic window of opportunity will close soon.

Presidential candidates should reflect this urgency in their election manifesto but a farsighted economic agenda is at odds with the short election cycles of the candidates.

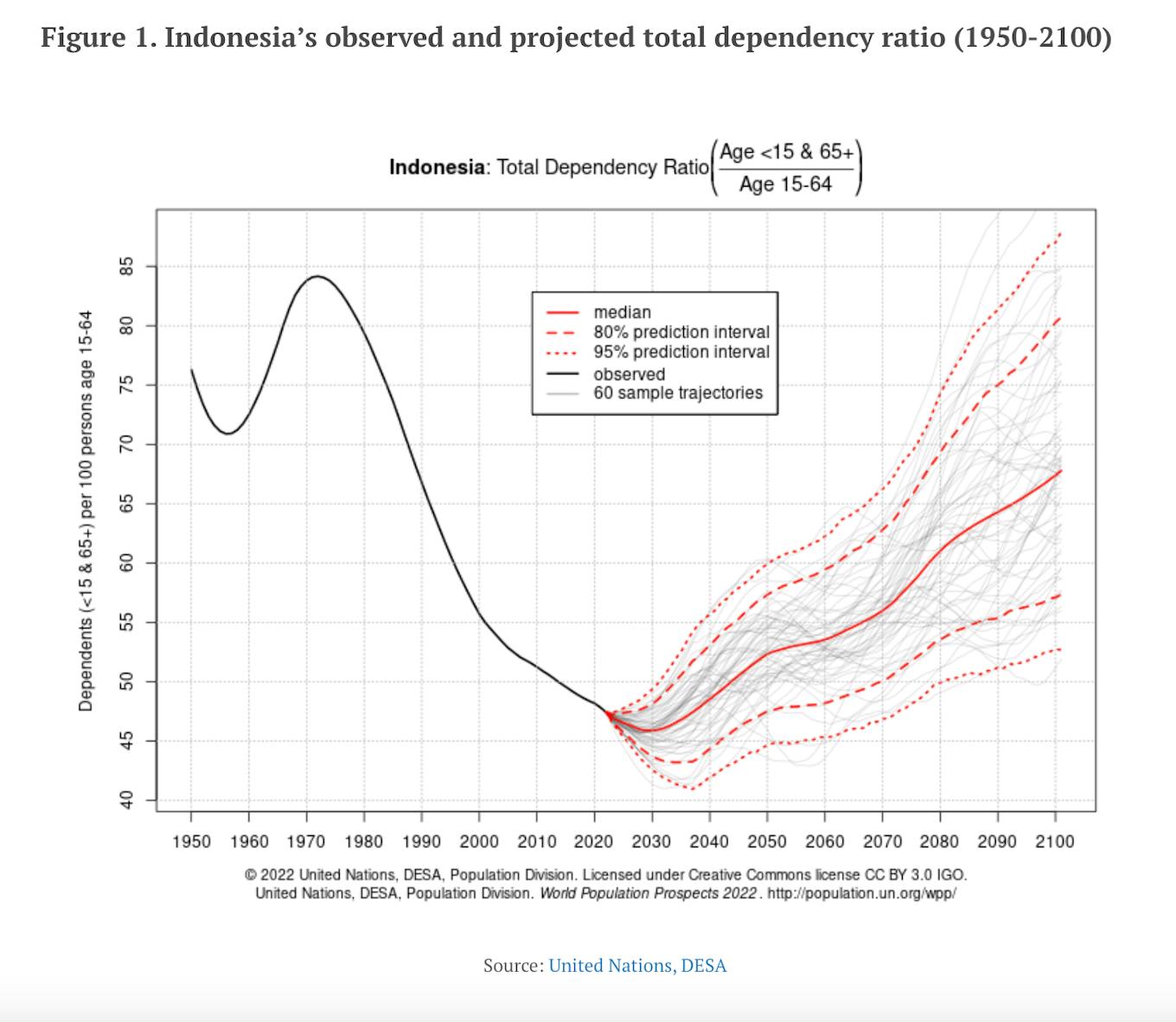

In less than 15 years but possibly as early as seven, Indonesia’s population will start to age, with an increasing number of dependents per working-age person (Figure 1). Its total dependency ratio (the number of people below 15 years old plus those aged 65 years and older, divided by those aged 15 to 64 years) was 47.2 per cent in 2022.

This ratio is expected to reach its lowest level, or the inflection point, between 2030 and 2040 before it will start to increase. There is no turning back: very few societies and countries where the data have been tracked in the last 50 years have become younger once they start to age. Even if Indonesia should become younger again, it will not happen anytime soon.

As a country’s population ages, economic growth starts to decline. The rate and the extent of the decline will depend on the foundation that the earlier, younger high-growth economy was able to lay, including for human capital, physical infrastructure, and governance.

Although an imploding working age population may be attenuated by a higher labour force participation rate, especially of elder workers (that is, those aged 65 or above), on average, older workers are not as productive and innovative as younger ones.

This usually translates to lower labour productivity growth and a slower rate of innovation. The natural growth rate of a country’s economy, which is the rate of economic growth that could be sustained over the long term and is determined by demographic changes and technical progress, will also decline. This results in a lower appetite for corporate investment and consequently, lower firm productivity.

What seems to be preoccupying policy makers now is how to “get rich before getting old”, as touted in the Grand Strategy for Indonesia’s 2045 Vision. This mindset must change: Indonesia should close its development gap by getting its foundations right, then get rich, not vice versa. The sequence of reforms matters.

President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) in his two terms has made tremendous progress in building certain structural foundations for the country – including in transportation, electricity generation, irrigation systems, regulatory reforms aiding investment, the financial and health sectors, and tax harmonisation.

This is his legacy in improving the welfare of Indonesians. However, there are big development gaps that Indonesia’s next president still needs to close in the next critical ten to 15 years, primarily laggard human capital and the eroding quality of governance.

“

The idea of becoming rich from downstreaming and expecting economic rents to automatically trickle down for the betterment of Indonesians by closing development gaps is simply naïve.

According to the World Bank’s Human Capital Index 2020, which quantifies the contribution of health and education to the next generation of workers’ productivity, Indonesian children will live up to only 54 per cent of their full productivity potential, compared to 88 per cent for Singaporean children and 69 per cent of Vietnamese children.

Human capital challenges, including scarring effects from the high albeit declining stunting rate (21.6 per cent in 2022), have dragged down Indonesia’s long-term potential growth since the 2000s.

Besides mobilising domestic resources and stakeholders, including identifying student learning levels that often fall short of student education levels and making up for significant learning losses during the pandemic, the key to improving Indonesia’s human capital will be allowing more foreign investment in education and health.

Indonesia has started taking steps in the right direction – for example, its Omnibus Law on Job Creation allows more foreign investment in hospitals. The next administration should continue such efforts.

Yet, the quality of governance in Indonesia has been deteriorating. According to the Corruption Perception Index, the fight against endemic corruption has backtracked since President Jokowi’s second term, with its worst decline in 2022. The Worldwide Governance Indicator portrays a similarly disappointing picture.

Indonesia’s full membership to the OECD, expected to be completed by 2026, could help difficult domestic reforms along, including in the areas of judicial reform, fighting corruption, upholding the rule of law and the values of democracy, as well as human rights protection. Indonesia’s next president could continue to push for Indonesia’s full membership to OECD.

Indonesia is currently obsessed with its so-called downstreaming strategy, for not one but 21 commodities in the next two decades. However, it needs to take a more rigorous cost-benefit analysis of such policies to ensure that the economic rents from the export boom accrue to the whole of society.

Importantly, this strategy must be executed under good governance while upholding multilateral trading rules. The idea of becoming rich from downstreaming and expecting economic rents to automatically trickle down for the betterment of Indonesians by closing development gaps is simply naïve.

Good governance is key to a just transition for Indonesia towards a greener economy, as there are power asymmetries between the winners and losers in this transition.

Globally, climate change impacts on the economy and populations are becoming more palpable: Indonesia is no exception. Climate adaptation is key. As the world’s fifth largest greenhouse gases emitter, Indonesia’s global role in cutting emissions must continue under the new administration.

The writing is already on the wall – if the current and next Indonesian governments do not double down on necessary but painful reforms in the next decade, the country risks missing out on reaching the status of a high-income country in a meaningful way.

Maria Monica Wihardja is an economist and a visiting fellow in the Media, Technology and Society Programme, the Regional Economic Studies Programme and the Indonesia Studies Programme at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.