An educational campaign to entice parents and their children to visit the S.E.A. Aquarium in Singapore and learn about ocean conservation in celebration of World Oceans Day has omitted the fact that the popular tourist attraction still houses more than 20 captive Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins.

The irony is not lost on Singaporean animal welfare groups, who say that letting these highly intelligent mammals go would be the best way to educate children about responsible ocean stewardship.

Starting on 2 June, the S.E.A. Aquarium – which is owned by Malaysian conglomerate Genting Group under the Resorts World Sentosa brand – is inviting visitors of all ages to see a photo exhibition, art installations and educational booths that, according to the press release, “advocate [for the] responsible use of oceans.”

The Ocean Fest 2023: One Shared Future programme runs until 13 August and targets parents and their “young ocean enthusiasts” with the opportunity to “delve deeper into marine biodiversity and conservation through fun and enriching activities” during the school holidays.

SEA Aquarium’s One Shared Future promotion claims: “Save their world and we save our own” [click to enlarge]. Image: Resorts World Sentosa

The programme, which costs S$43 (US$32) for adults and S$32 (US$24) for children, invites visitors to “examine the interdependence between humans and oceans through the lens of marine life affected by human activity,” the press release sent to journalists reads.

It includes art installations that show how marine creatures are affected by plastic pollution and booths that aim to inform the public about environmental efforts made by local youths to protect local waters and recruit members of the public to sign up as volunteers.

But there is no mention in the press release of the resort’s dolphins and the role these marine mammals play in keeping oceans healthy in the wild – or how they are affected by spending their lives in captivity, although in response to queries from Eco-Business, RWS has said its dolphins are given the “highest quality care”. Their cognitive and physical functions are encouraged through learning, exploration and play, wh-ch provides them with a “a healthy and thriving environment,” it added.

“Our viewpoint is that well-run marine life park facilities not only provide visitors with engaging experential opportunities to learn more about the marine world, but also inspire them to take action to contribute to conservation efforts,” it said.

“Research has shown that dolphins can indeed thrive in marine parks.”

Its facility, RWS said, is accredited by the Association of Zoos & Aquariums (AZA), a non-profit that evaluates zoos and aquariums, and is a member of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA).

Scientific research, however, also points to how dolphins, when lacking social, visual and auditory stimuli in enclosures 200,000 times smaller than their natural range, are believed to suffer from the stress of confinement. For dolphins, captivity has been likened to psychological torture, because these mammals are self-aware, hyper-social and experience a wide range of emotions, including empathy.

Resorts World Sentosa acquired 27 wild-caught dolphins from the Solomon Islands in 2008 and 2009. Four have died, either in transit or from disease while in captivity. The rest remain at the aquarium, where visitors pay SG$78 (US$58) to see them, or more to swim with them.

Local animal welfare groups have long opposed holding the dolphins at the resort. When news of their capture and transfer to Singapore first emerged, Louis Ng, the founder of animal welfare charity Animal Conserns, Research and Education Society (ACRES) and now a politician, started a widely-supported petition to stop Singapore importing the dolphins, stirring public debate over the morality of keeping highly intelligent creatures in captivity for entertainment.

ACRES’ “World’s saddest dolphins” campaign. Image: ACRES

ACRES was joined by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) in voicing its opposition to dolphin captivity, which SPCA called “unabashed animal exploitation”.

“Resorts World, please let the dolphins go” went the campaign slogan, which was emblazoned on t-shirts and worn by animal rights activists in a rare show of public protest in the conservative city-state.

But despite the backlash, the dolphins arrived. Twelve years on, the movement against RWS’s captive dolphins has gone quiet.

This is despite gathering momentum to free some of the estimated 3,000 dolphins still kept in aquariums and marine parks across the world.

Last October, South Korea released the last of eight captive dolphins – an Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin named Bibong – in the waters off Jeju Island after having it in an aquarium for 17 years. Its government took responsibility for ensuring that the dolphin would safely acclimatise to the natural ocean environment.

In March this year, the United Kingdom celebrated 30 years free of captive dolphins and whales. There are still continued calls to legally ban the import and display of captive dolphins and whales to prevent risks of a backslide.

S.E.A. Aquarium’s Dolphin Island exhibit made international headlines in 2019, when a dolphin was filmed repeatedly hitting its head against its enclosure wall (S.E.A. Aquarium said at the time they were “uncertain” of the source of the video) The casino resort which owns the aquarium has always defended its position, saying that well-run zoological facilities “provide strong and inspiring messages to visitors and can make a tangible difference to animal conservation ). “There will always be divergent views about animals in human care and in a zoological environment,” its spokesperson once said.

‘Greenwashed’

Aarthi Sankar, SPCA’s executive director, said that the park’s One Shared Future campaign amounts to “greenwashed messaging” as it tries to lure parents looking for fun, informative experiences for their children, who are unaware of the cruelty behind dolphin captivity.

“Understanding the potential harm caused by captivity and prioritising the welfare of animals should be paramount in their decision-making process. We should always research the facilities and the work they do before making informed decisions about whether or not to support such establishments,” she told Eco-Business.

Sankar pointed out that dolphins’ complex physical and psychological needs cannot be met in captivity. In the wild, these mammals – which are regarded as second only to humans for intelligence – have vast oceanic territories and engage in complex social interactions, hunting and migration patterns.

“Confining them to small enclosures can lead to stress, sensory deprivation and reduced lifespan,” she said.

Public opposition to keeping cetaceans in captivity has grown steadily over the past decade, fuelled by documentaries such as Blackfish, which detailed the psychological harm inflicted on captive Killer whales at Sea World, a popular attraction in the United States.

Anbarasi Boopal, ACRES’ co-chief executive, noted that more than 20 territories have regulated or banned the capture and detainment of dolphins and whales for public entertainment. In 2016, the US National Aquarium in Baltimore, announced that their dolphins would retire to sea pen sanctuaries, due to public opposition to keeping marine mammals in captivity.

TripAdvisor advisory section for Dolphin Island, S.E.A. Aquarium’s dolphin exhibit [click to enlarge]. Image: TripAdvisor

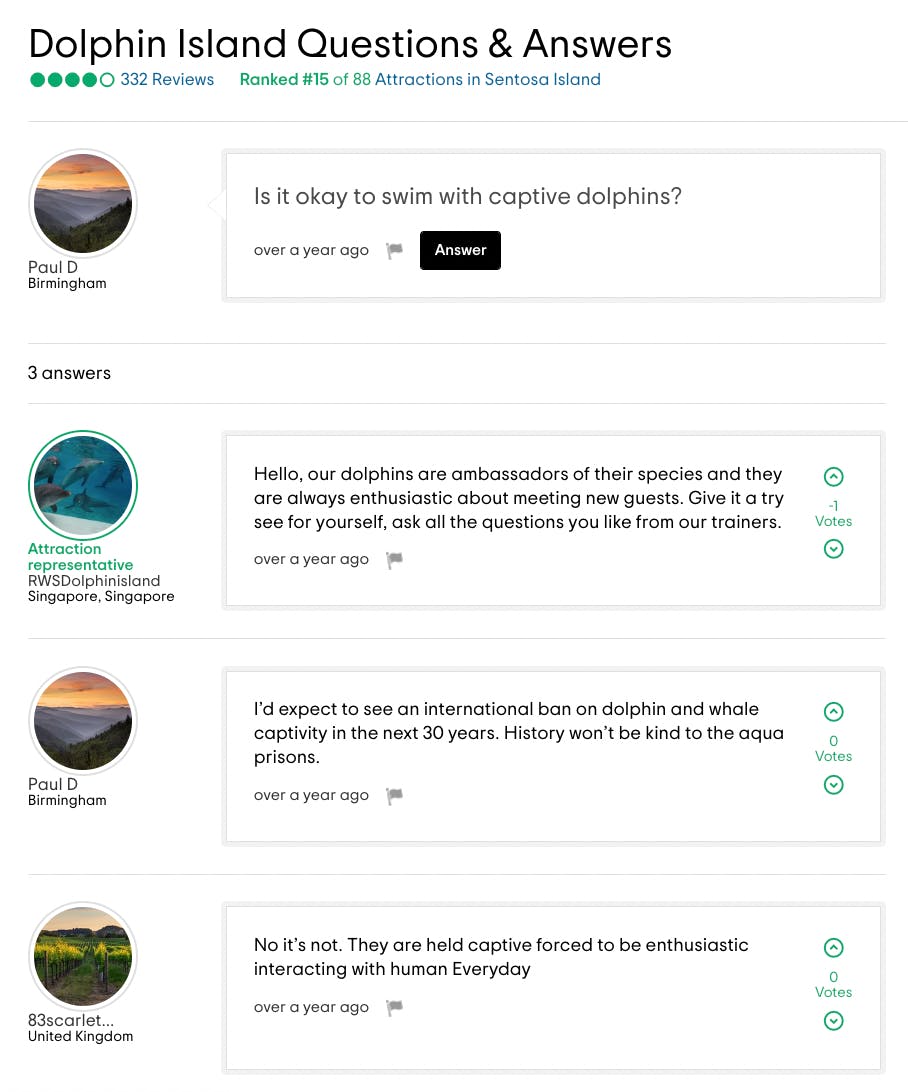

Travel website Trip Advisor mentions marine mammals in its animal welfare policy – although it does feature Dolphin Island as an attraction (see RWS’ response to a question about dolphin captivity posted by a user) – while 4 July is now a world day for captive dolphins to highlight their plight, Boopal noted.

“Ultimately, there is a lot more consensus and public sentiment around capturing and keeping such intelligent animals in captivity for the entertainment purposes. It is not justifiable, considering the welfare issues they face as a result,” she said.

“By paying and visiting dolphins in captivity, the unaware public are playing a direct part in the cruelty, starting from capture from the wild, to stress in captivity.”

Boopal points to an online study by George Mason University in the US from 2015, which found that over 80 per cent of respondents felt that dolphins should not be in captivity for entertainment purposes.

“It is really high time for change. We sincerely hope that RWS will change its mind, with a genuine commitment to the cause of marine protection and animal welfare by ending the keeping of dolphins in captivity, and look into rehabilitation options,” Boopal said.

RWS, in its replies, cited a three-year AZA-backed of cetacean welfare in 43 zoos and aquariums in seven countries, including Dolphin Island, which found that the quality of human care directly impacts cetacean welfare more so than other factors.

Quoted in the study, Dr. Lance Miller, vice president of conservation science and animal welfare research at the Chicago Zoological Society, said: “The general public has a perception that dolphins need a large habitat because they think of them living in the wild. But if you’re a human, would you rather live in a cozy house with lots of things to do or a large place with nothing to do?”

RWS said its dolphins have “acclimatised to human care [after years spent at the facility], are healthy and well-settled, and we are confident they will continue to thrive.”

The company noted that in the wild, dolphins can become victims of predation, are killed as by-catch by fishing fleets, and are exposed to pollution.

At S.E.A. Aquarium, the animals have formed close bonds with their trainers, who “support the animal’s physical and mental well-being”.

“We believe we are doing what is best for our dolphins and will continue to do this,” the company said.

The company had previously argued that the exhibit gives visitors a rare opportunity to see animals they would never see otherwise, although animal welfare groups have pointed out that dolphins are indeed found in Singaporean waters. A sighting of three Indo-pacific humpback dolphins was recorded off the coast of Singapore’s Lazarus Island in 2020. In 2018, an ACRES team rescued a dolphin that had been caught in fishing gear.

Do Singaporeans care?

Some question the level of public concern for captive dolphins in Singapore, a highly urbanised city-state where concern for nature in general has been called into question, such is the psychological divide between consumerist, high-rised living and the natural world.

“I don’t think Singaporeans know enough to care about dolphins in captivity, however, when given the right information and knowledge - people will start asking questions,” said Pamela Ng, a master’s student in biodiversity conservation at the National University of Singapore.

When people start asking questions, “that will prompt the care that we need for wild animals in captivity,” she said. “Most of the population are rather oblivious at the moment - due to a serious lack in awareness.”