Despite half of Asia Pacific investors expressing high concern about climate change, most (68 per cent) do not consider companies lacking plans to reduce their Scope 3 emissions to be risky investments.

This was a key finding from a global survey of 150 institutional investors from over 100 companies across the United States, United Kingdom, Singapore, Japan, Australia, Hong Kong and Belgium by environmental campaign group Market Forces and New York-based market researcher NewtonX, released on Monday.

28 per cent of the respondents were based in Asia Pacific. Half of them had US$100 billion or more assets under management, a quarter of them are part of the C-suite and over half can either influence decisions or are the final decision makers.

To continue reading, just sign up – it’s free!

- Get the latest news, jobs, events and more with our Weekly Newsletter delivered to you free.

- Access the largest repository of news and views on sustainability topics.

- You can publish your jobs, events, press releases and research reports here too!

Newsletter subscribers do not necessarily have a website account. Please sign up for free to continue reading!

Scope 3 emissions refer to the indirect emissions from a company’s supply chain and typically account for the bulk of its emissions. Scope 1 and 2 emissions are those from a firm’s own operations and energy use respectively.

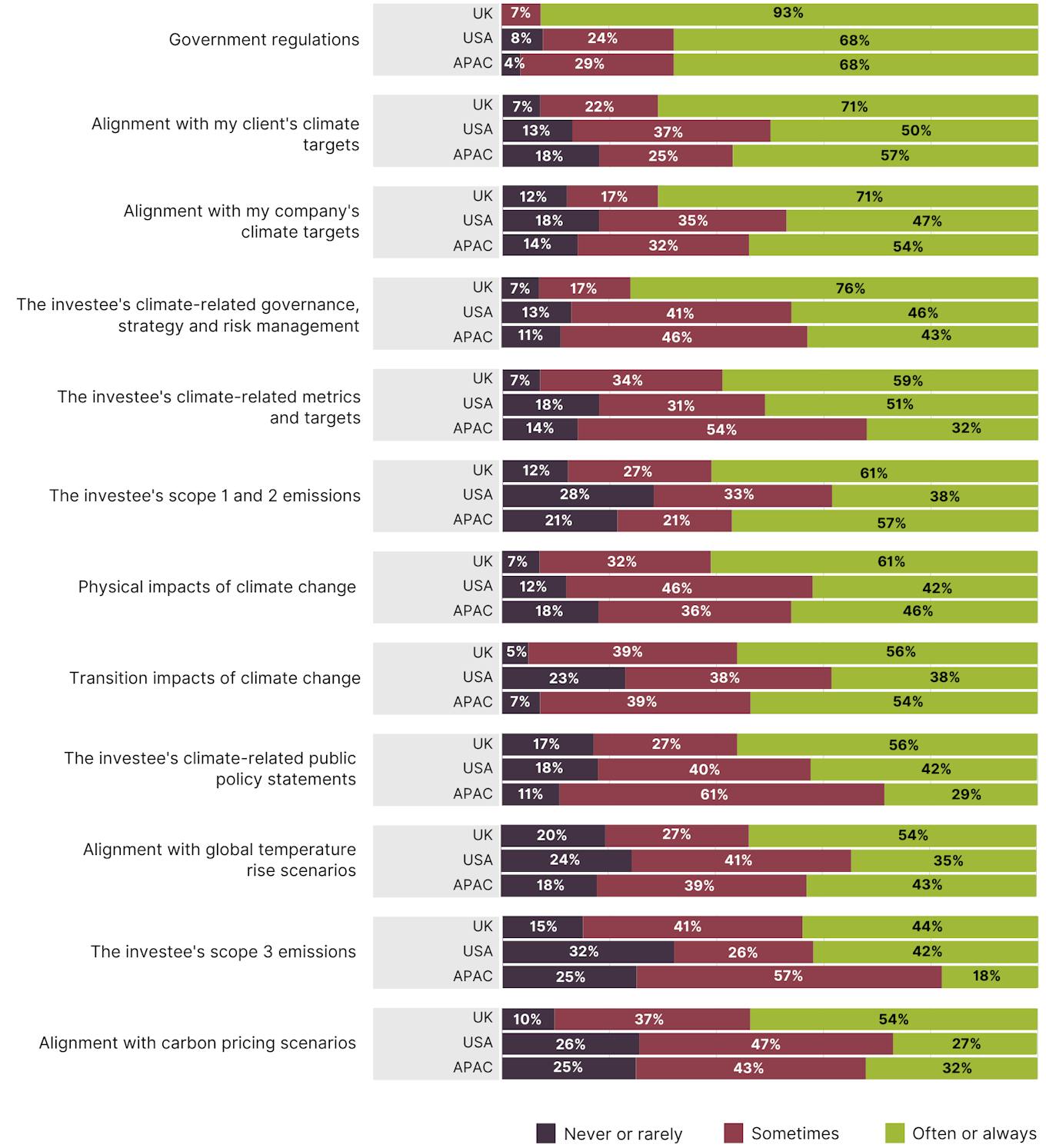

While over 40 per cent of investors in the UK and US “often” or “always” consider Scope 3 emissions when assessing investments, only one in five of Asia Pacific investors do the same.

The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) standards – dubbed the new global baseline for sustainability reporting – will eventually require companies to disclose their Scope 3 emissions, after a one-year grace period. In the Asia Pacific region, jurisdictions like Singapore and Australia are starting to make ISSB reporting mandatory for large listed and non-listed companies.

Government regulation appears to be the top concern for most Asian investors (68 per cent) when evaluating their investments. This is followed by alignment with their client’s climate targets (57 per cent), their investee’s Scope 1 and 2 emissions (57 per cent) and alignment with their own company’s targets (54 per cent).

Across all three geographical regions, investors also rarely mark down companies for continuing to facilitate new fossil fuels development or over-relying on unproven technologies to cut emissions.

Regional breakdown of climate risks considered by investors when assessing an investment. Investors were most concerned about government regulation, but few in Asia are diligently factoring their investee’s Scope 3 emissions into their decisions. Source: Market Forces’ Investor Disconnect on Climate Risk report

Based on the study, Asian investors – like their peers in the West – are predominantly relying on their companies’ internal modelling and analysis (61 per cent), investee disclosures (50 per cent) and media articles (50 per cent) to assess their climate risks and opportunities.

In Asia, relatively less investors use International Energy Agency (IEA) scenarios modelling (18 per cent) as well as Science Based Target initiative (SBTi) criteria and verification (14 per cent), compared to their global counterparts.

Rose Tehan, report author and analyst from Market Forces, told Eco-Business that executives who are failing to assess Scope 3 emissions identified two key barriers to incorporating climate risks in their decision-making: a lack of skills to apply climate scenarios modelling and analysis as well as a lack of relevant data from investee companies.

“Other key barriers identified by Asia Pacific executives include a lack of information from companies about their climate management strategies along with insufficient data and emission reduction targets,” she added.

The report notes a well-known problem has been a lack of regional pathways in, for instance, the IEA’s Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario, which makes it difficult to incorporate it into most valuation models.

More concerned with reputation than climate risk

“Our research found that executives at many of the world’s largest investment firms are more concerned about their reputation than climate risk,” said Tehan.

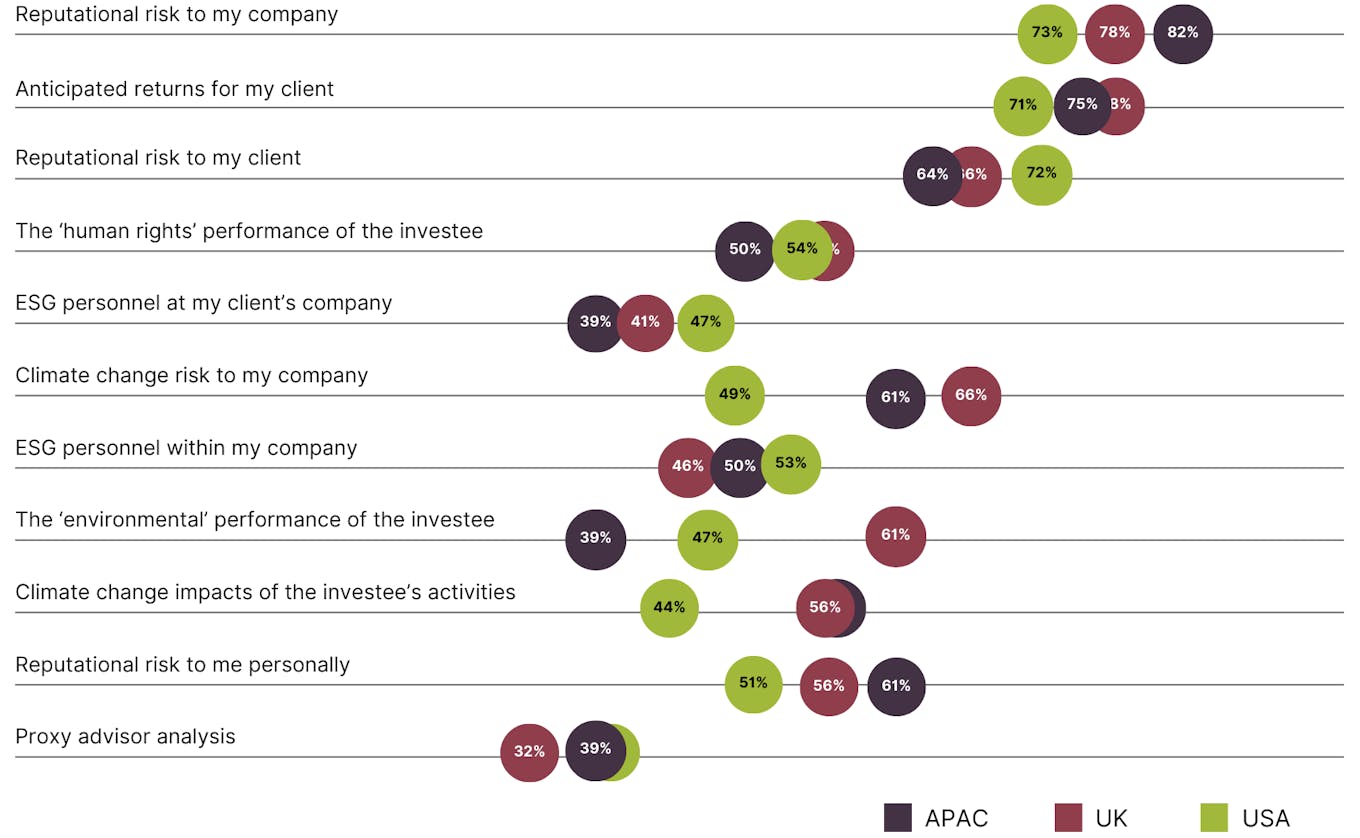

This finding was particularly pronounced in Asia Pacific, which had the highest proportion of investors (82 per cent) who indicated that decision-making was influenced by reputational risk to their own companies.

Regional breakdown of factors with “high” or “very high” level of influence on investor decision making. For Asian investors, the risk of reputational damage to their own companies had the most influence over their decision making, while the “environmental” performance of the investee had the least influence. Source: Market Forces’ Investor Disconnect on Climate Risk report

While most Asian investors generally factor climate risk into their investment decisions, with two in three (61 per cent) viewing it is highly influential, this refers to climate risk faced by their own companies and not those they invest in. Just 56 per cent of Asian investors view the impacts of an investee’s activities on climate change, such as whether it is a coal miner or oil and gas producer, as a highly influential factor.

The environmental performance of investee companies was the least influential consideration (39 per cent) among Asian investors, compared to their peers in the UK and US.

“Fund managers are less concerned about climate risks than they are political or activist pressure. This is almost entirely because climate risks have very little impact on asset performance,” said one US hedge fund manager who was quoted in the report.

When asked what would help investors in high-risk companies engage more effectively, many respondents said that they wanted an authoritative, objective and standardised body of data they could use to quantify climate-related risks and impacts, including risks associated with reputational damage or regulatory changes.

“Climate risk is still not a widely adopted and standardised risk topic,” read one of the responses from a UK bank executive. “Unfortunately there is a lack of consistent data across market caps and industries. As with any investment, there is a high [degree] of subjectivity, so until that risk can be pretty accurately quantified (and universally agreed upon), it will be difficult to get the industry to agree.”