Celine Lim and the community-based environmental campaign group she runs, Save Rivers, were staring down the barrel of a financially crippling law suit.

Malaysian timber giant Samling was suing Save Rivers for defamation, seeking RM5 million (US$1.1 million) in damages for articles on the organisation’s website that raised concerns over the treatment of local communities living in areas under the company’s management.

But on 18 September 2023, the day the trial was scheduled to begin, 25 months and four rescheduled trials after Samling sued, the two parties reached a settlement.

Untuk meneruskan membaca, hanya daftar - ia percuma!

- Dapatkan berita terkini, pekerjaan, acara dan banyak lagi dengan Surat Berita Mingguan kami dihantar kepada anda secara percuma.

- Akses repositori berita dan pandangan terbesar mengenai topik kemampanan.

- Anda boleh menerbitkan pekerjaan, acara, siaran akhbar dan laporan penyelidikan anda di sini juga!

Pelanggan surat berita tidak semestinya mempunyai akaun tapak web. Sila daftar percuma untuk meneruskan membaca!

The resolution was hailed as a minor triumph for conservation and Indigenous peoples in Malaysia in the ongoing battle to protect Sarawak forests from loggers. Over the past 20 years, Sarawak has lost more than a quarter of its forests, which Indigenous people in the region have historically depended on for their food, health, livelihoods and culture.

That Samling dropped its lawsuit was testament to Save Rivers’ ability to galvanise support from other Malaysian and international non-governmental organisations – 160 NGOs had called on Samling to withdraw the case, pressure which led to a series of investigations into Samling’s forestry practices by certification bodies.

“

Indigenous communities have a lot to teach the world about how to synergistically live with their environment and manage natural resources.

Celine Lim, manager, Save Rivers

It was also evidence of Lim’s knack of finding amicable resolutions to seemingly insurmountable problems. Samling is one of Malaysia’s largest timber companies, worth in excess of US$1 billion and armed with considerable political muscle.

Lim, who is an Indigenous member of the Kayan tribe from Long Pilah in Baram, a region of 283,500 hectares (ha) in northern Sarawak, is a believer in conflict-free activism as an agent for change.

“At the same time as we are criticising [governments and businesses], we are also learning how to build bridges,” says Lim, whose advocacy efforts earned her a place on the Eco-Business Sustainability Leadership A-List 2023, a who’s who of Asia’s most influential sustainability professionals.

Though she is not at liberty to talk publicly about the Samling case, Lim’s group has prior experience of peacefully standing their ground against powerful opponents.

Save Rivers, as its name suggests, was born out of a resistance movement to stop a massive hydroelectric dam on the Baram River, which would have flooded 40,000 ha of forest and cost 20,000 Indigenous people their homes.

Save Rivers’ protest on behalf of 26 communities of the Indigenous Kenyah, Kayan and Penan peoples involved one of the longest running blockades in Malaysian history. For almost two years the group formed a constant barricade to stop the dam-builders from accessing the Baram River construction site.

The blockade was widely covered by the local and international media, which fuelled interest in Save Rivers’ cause and led to more supporters joining in the action. In tandem, Save Rivers lobbied international leaders to stop the dam.

On 20 March 2016, Sarawak officials cancelled the construction of the Baram dam, marking the end of one of the most successful environmental defence campaigns in recent times in Southeast Asia.

At the heart of the cause Lim’s community continues to fight for is their right to live on their ancestral lands. When timber licenses are granted to companies by the Sarawak Forestry Department, the forests that Indigenous peoples have depended on for generations are not recognised, only the plots of land that they live and farm on.

“Legally, we don’t have the land title [for the forests]. But historically, we’ve been here for generations – and we have the ancient burial grounds to prove it,” she says. “When you limit the land forest-dependent communities are entitled to to the land they live on, you steal their identity.”

Lim took on the role of manager of Save Rivers in 2019. The organisation has just five staff, and a variety of funders, including the Green Livelihood Alliance, a Netherlands-based funder that funds NGOs all over Southeast Asia, and works with NGO groups including The Borneo Project, a United States-based group working protect Borneo’s forests and people against industrial logging.

In this interview, Lim talks about her ongoing struggle to protect her peoples’ land from logging and dams, and explains why the loss and damage fund brokered at the recent COP28 climate talks is unfair.

How has the potential for conservation groups to resist land encroachment changed in Sarawak in recent years?

Thirty years ago, the situation was dire. International sustainability certification schemes that give us a form of check and balance to police the development of forests did not exist. Logging was done by concession, and decisions were made among the elites. But now, entities that source forest products from Malaysia demand chain of custody verification, and that has benefited civil society organisations like ours. We can use certification schemes to push back, as the pressure on Malaysia to certify its timber as sustainable for the international market has increased.

Tell us a bit about the region of Baram in northern Sarawak and why conservation is so important.

Baram is a region of 283,500 ha, about three times the size of Singapore, of which 79,000 ha are still untouched, pristine forest. Our conviction is that this 79,000 ha of forest – which is Sarawak’s last intact forest – must be protected.

We have conducted our own research to assess the flora and fauna in this area – the Baram Heritage Survey. This is a counter response to the Environmental Impact and Social Assessments and High Conservation Value surveys that have been used in the area, which concluded that none of the communities are dependent on the forest anymore.

The Baram Heritage Survey was conducted with help from researchers from Universiti Malaysia Sarawak and members of the local community, who were trained to run the survey, and based on a research model used in South America. We needed evidence to show that the community still depends on the forests.

What is your main grievance with the way the land is managed in northern Sarawak?

The main point of contention is how Indigenous communities are always sidelined when land use decisions are made in Baram.

And while the logging industry in Baram has been in operation for 30 to 40 years and is a big natural resource hub for the regional and national economy, Indigenous communities are still marginalised when it comes to basic amenities.

Even today, we don’t have proper road access to our communities, and must use logging roads; the closest of the communities we work with is eight hours by 4X4 vehicle.

There are no proper health services. There is no telecommunications. We are literally offgrid. Though there are some parts of the village where we have access to free internet, but when it rains, forget it.

Managing conflict is something you have done effectively in your work. How?

I wouldn’t say we are doing it well, but we are just getting on with what needs to be done. The people we work with approach the land use issue from very different angles and points of view. When sitting down with the forestry department we have to be very forthright and honest, and appreciate that there are always options we need to consider. It’s mentally exhausting.

Compared to our counterparts in Indonesia and the Philippines, I would not say we are as confrontational. Yes, we have used blockades and demonstrations, but never violence. And we have faced down insidious tactics to silence us [such as Samling’s Strategic Lawsuit against Public Participation, or SLAPP suit].

“Stop the chop”: a group of protesters from Indigenous communities in northern Sarawak demonstrates against a lack of consent given to companies to develop their customary lands. Image: BFM

Tell us about how Save Rivers successfully blocked the construction of the Baram Dam, which would have resulted in 20,000 Indigenous people losing their homes.

It started out as a movement from within our communities, but we also tapped into numerous international alliances to help us. We have always seen ourselves as living in two worlds – as a proud Indigenous community, but also part of the wider global community. We have had to understand the international discourse over certification, climate change and other global environmental issues to frame our narrative and further our cause. This is something we learned during the anti-Baram dam campaign.

In that campaign, we created a blockade at the dam site for almost two years. It attracted a lot of attention. Filmmakers and the media visited the site, which created a large supporter base for the campaign. We insituted a rotation system so that there were always people manning the blockade. We were an immovable force. People would come and go, and communicate from the dam site to the outside world. Continually telling our story was critical to keep the campaign alive.

Another crucial element was fun. There was a lot of music, dancing and food. People from the community would come in and cook for everybody on the blockade. There was a communal spirit that kept us going. There was also legal training for the community on site. The blockade was definitely not boring.

It was also not confrontational. What helped diffuse any conflict was that people who worked for the authorities who wanted to build the dam had family and friends who were part of the resistance movement on the blockade. That wasn’t necessarily a conscious tactic, it just worked out that way.

Meanwhile, we were lobbying international groups. We gave a petition signed by 10,000 community members to the chief minister at the time at an event in London, which was particularly effective at getting our message across.

Is there a risk that the Baram Dam could still be built?

The word that was used in 2016 was “shelved”, which means there is a chance that it could still be built. But we haven’t heard anything about a revival of the Baram Dam project.

That said, the authorities are now trying to rejuvenate another dam project that was part of the 12 mega dam projects earmarked for Sarawak. Because of the anti-Baram Dam campaign, a number of other hydroelectric power projects were postponed – the campaign had a ripple effect.

The Bakun Hydroelectric Dam in Sarawak, one of 12 large hydroelectric dams that have been planned for the region. Image: IEEE Curtin Malaysia Student Branch/Facebook

We have responded to a claim made by the current Premiere of Sarawak that people in the area want a cascading dam on the Tutoh River [Sarawak premier Abang Johari Openg has said the dam will generate 35,000 megawatts of surplus power, which can be sold to other regions]. We are demanding a roundtable stakeholder meeting. The burden of proof is on the government to prove that claim – that the people want the dam, which we believe is not the case.

Sarawak premier’s has claimed that the cascading dam can prevent excessive crocodile breeding in the river, and that there is an “infestation” of crocodiles in the river – but we have seen no data to back up this claim.

We are also concerned about the impact of the cascading dam on Mulu — which is a UNESCO World Heritage site — as the Tutoh river is connected to the national park. A petition opposing the dam has collected 500 signatures [as of 16 January].

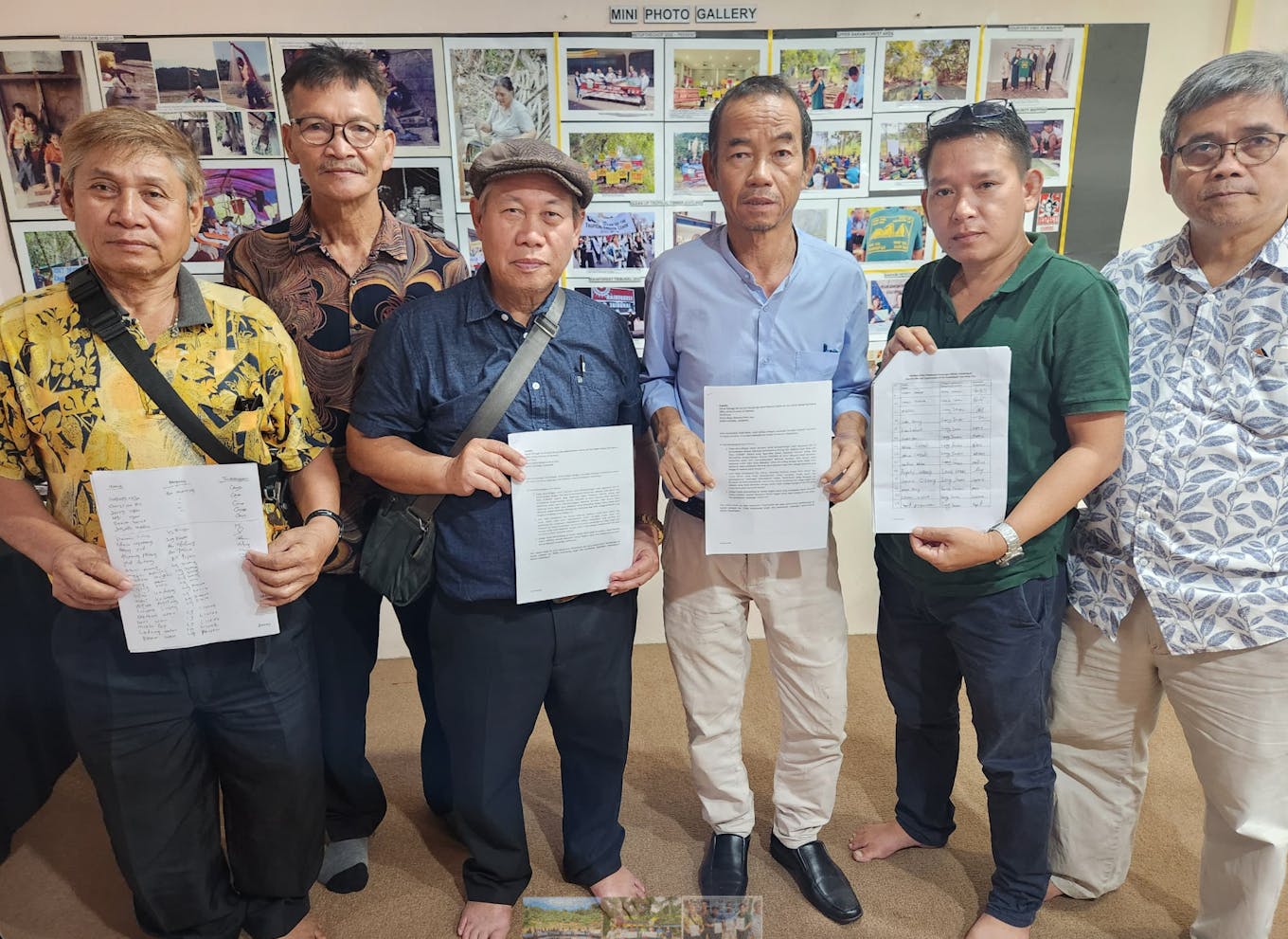

Men from representing the communities of Tutoh and Apoh hold a signed petition that opposes the construction of a cascading dam. They say the dam will be built without their consent and may effect the Mulu National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Image: Save Rivers

What’s your view on the loss and damage fund, and the Global North paying to help developing countries adapt to climate change, which was negotiated at the COP29 climate talks?

Indigenous communities are victims of this climate crisis, and we’re learning how to combine modern science with ancestral knowledge to adapt to climate change. The Global North historically has responsibility for climate change. It has been saddening to see the Global North setting the terms for the dispersal of the loss and damage fund, which was supposed to be its way of remedying and apologising for the climate crisis, and the colonial history that has brought us to where we are today. But it feels like the Global North counterparts have been highjacking the process, and has made it very difficult for the Global South to tap into climate adaptation finance. The Global South should have much more influence over the process.

What does the world have to learn from Indigenous peoples and the traditional way of life?

We believe that Indigenous communities have a lot to teach the world about how to synergistically live with their environment and manage natural resources.

Right now the world is talking a lot about sustainability. But for the longest time, living in balance with nature was taught to us [Indigenous people] at a very young age – how to respect our environment and recognise that we are just a small part of a whole, and to respect the environment as you would another person.

If you go to Baram, you will notice a big difference in people’s relationships with the environment and how we farm the land. Industrial agriculture uses the environment as a commodity. Indigenous peoples practice polyagroforestry, which is more in balance with nature.

I remember a story about a very prominent businessman who looked out over his monoculture plantation, and said ‘Behold, look at the beautiful forests’. He overlooked the fact that the river and forest had been destroyed to make way for his plantations.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Celine Lim was one of 10 sustainability leaders selected for the Eco-Business A-List 2023. Read our stories with the other winners here.